A look into Budget Gateway Interface (BGI).

There are times in life when you write Java, PHP, or Ruby to build out your web applications. Then there are times when you really just want to write in a language you love. Don't get me wrong, I enjoy writing all the mentioned languages to some extent. But my true love, as I've said on other parts of my website, is C.

So you want to write a web application in C

I've created a custom server before, but this time I wanted to spend more time on the application layer. So I decided to try to learn something new. Specifically, CGI scripting. After a quick google search and reading a little bit about CGI I found out that CGI scripting is actually pretty simple.

The gist of CGI is that the web server places your query parameters into an

environmental variable, and you read and parse that information for the URL and

parameters in the request. If it's a POST or PUT request, then the incoming

data comes in on stdin. Which I personally thought was quite cool and makes a

lot of sense.

Parsing query variables isn't hard, but as I said above, I wanted to spend time on the application layer. So I checked out the libraries listed here and chose to use qdecoder. Once that was in place I created my Makefile, and I happened to stumble onto a few good blog posts and examples on making Makefiles to deal with a typical project structure (src,obj, and bin directories). Here's one of the interesting lines in it:

OBJECTS := $(patsubst src/%.c,obj/%.o,$(wildcard src/*.c))

TARGETS := $(patsubst src/%.c,bin/%.cgi,$(wildcard src/*.c))

$(TARGETS): $(OBJECTS) $(UTIL)

${CC} ${LINKFLAGS} -o $@ $(patsubst bin/%.cgi, obj/%.o, $@ ) $(patsubst %, obj/%.o, $(UTIL)) ${LIBS}

While not everything shown here is defined (if you really want you can look at the

Makefile source here ), the cool part is that the targets and the objects are

being created based on the source filenames. The line $(patsubst src/%.c,obj/%.o,$(wildcard src/*.c))

takes all the C files in the src directory, captures their names, then creates a

string pointing into the object directory with the same name. For example, a file

called heartbeat.c stored in the src directory, would be picked up by this, and the

src and .c portions of the string replaced with obj and .o. The same logic

is then applied to the TARGETS which all end in .cgi and live in the bin

folder.

The actual make targets are created from the last two lines that specify that all

TARGETS depend on all the objects (as well as some utility classes) and then we

use the $@ and $< operators in Make to retrieve the target and dependencies

for each target being created.

After I had my project structure setup, I started in by looking at the excellent examples of qdecoder to determine how I would write my programs. I came to the logic that each of my CGI scripts should be as simple as possible, doing a single job, and that I had everything I needed. Well, except a database.

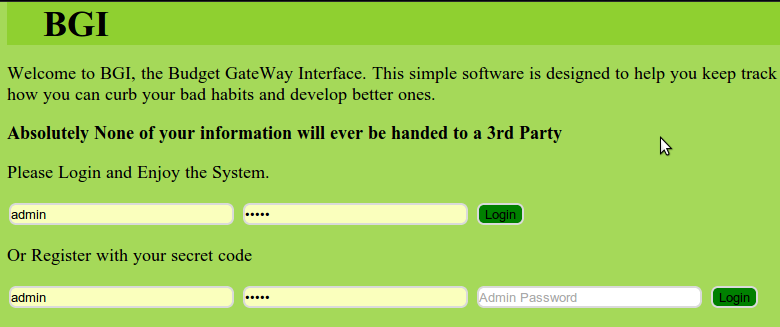

The Index Page

It was simple to create a login and registration form and wire them into

CGI. The forms were simple and so was the data validation.

Storing the data

I initially thought about using mySQL as my database backend. I used it in green-serv and am familiar with the C API for it. But, something I didn't like about using mySQL is that my current system's has 2 versions of mySQL installed (5.5 and the bleeding 5.6) and that had foobarred my Makefile in green-serv a bit and I wanted to avoid that. So I decided that it would be fun to roll my own (I know, reinventing the wheel, shame shame).

As such I defined an exceptionally simple format for storing the data:

data/ .users <username>/ accounts <account name 1> <account name 2> ... <username 2>/ accounts ...

The data directory consists of a single index file to store the users and a hash of their password (yes, no salt, I know it's not secure, this is a play project). Once a user exists, they are given their own directory with an accounts file inside. This accounts file acts as an index for the balances and names of a users accounts. And then the line items stored for each account are placed into a file named after that account.

Here's an example of what some of that data looks like:

.users

admin 63876434

admin/accounts

1 checkings 7.000000 2 food 14.000000 3 Home Supplies 10.000000

admin/checkings

1404876690 test 1.500000 44.475800 -73.211900 1405386959 Something 1.00 44.486497 -73.212105 1405477153 test 4.50 44.486567 -73.212207

The data being stored in the account file itself is simple:

<epoch time> <item name> <spent> <latitude> <longitude>

You might be wondering why there's latitude and longitude built into this. The answer is that when I had the initial idea for this appplication, I wanted to access it from a phone, right after I bought something, and then be able to track where I was spending most of my money (hint, buying lunch everyday is expensive).

Visualizing the Data and the display itself

To show the information I turned to my goto for static websites, Harp. It was easy to create a very simple website with minimal styling that functioned as the interface to my budget tracking habits. It doesn't look that good, but it does look like this:

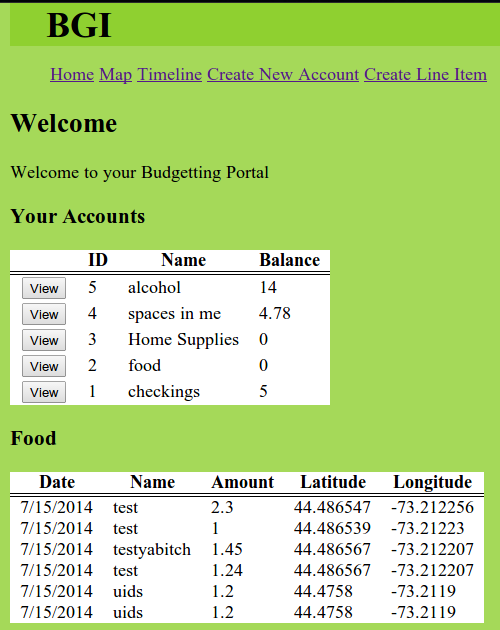

The Application Page

The main application page (after the login pictured above) consists of a simple lists of your accounts and their balances. By clicking on the View button for each account, you can see a list of line items spent. Because of the way the data is appended to the end of the datastore files, they are naturally ordered by date and so displaying them in order is merely a matter of output.

The Metrics Page

One of the most important parts of any data is displaying it in a form that is easily digestable. When you're trying to track your spending habits there are a lot of ways you can do it. I've elected for 4 simple charts.

-

Pie Chart of account balances.

-

Timeline of spending per day (total, not by account)

-

Spending by Month (do you spend more in the summer? winter?)

-

Spending by day of the week (should you stop partying* on friday?)

The most interesting to code of these graphs was the timeline. I used Chart.js for each of the graphs, all of which were straightforward since they had obvious labels (months and days), but when you construct a line graph you need to have all of your labels, and then the indices of the data for the label must match the indicies of the labels. (The label for the first data point must be the first label and etc) This is slightly problematic when you don't actually know the days that the user has bought things on. Furthermore, if the user didn't buy something one day, then you still need to reflect that 0 point even though you don't have any data for it.

This isn't that hard to figure out if you give it a moment's thought, but it was fun to implement. Essentially, you need to determine the minimum and maximum times over your dataset, then create all the labels and buckets for all the data points. Once you have that, you need to map your data points into the right buckets. If you're curious on the actual implementation, checkout timeline.js around lines 104 and on.

*By partying I mean coding late into the night and eating pizza of course.

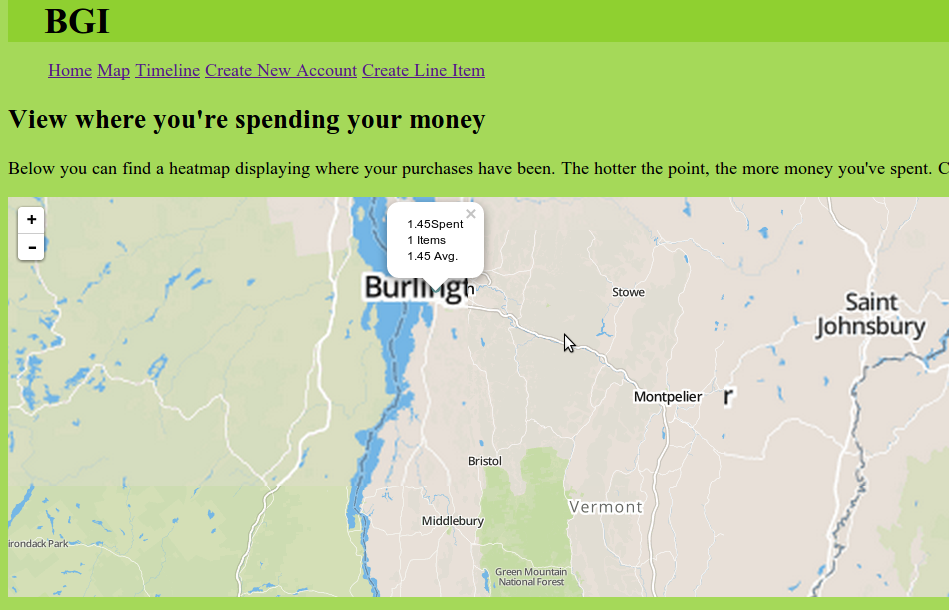

And the map Page

And lastly, to try to figure out where I'm spending too much money, I need to know where I'm spending it! A map is the best way to view geographically oriented data, so I used Leaflet.js to create a simple and easily marked up map. I personally prefer Leaflet over Google Maps, not just because it supports tons of tilesets, but because I had a great success in using it to display a lot of data for my work on Green Up.

Some final thoughts

Overall this project was tons of fun. Using CGI really forces you to think about HTML as being stateless (which it is). And to construct easily usable API's to talk to for the data you need. I'm lucky I was using Harp since the use of partials really assists with creating error pages to respond to badly formed requests to the CGI (As oppose to creating a whole seperate HTML page to do so).

CGI is fast. The queries to retrieve information for the javascript happen in about 23-30ms almost always. The power of a compiled binary executing on a server is obvious when you compare it to php scripts that would be doing the same thing. The only overhead I really have is the process for the CGI starting up itself, which I could easily fix by using FastCGI. I imagine that if I continued to expand this application, the File IO would probably end up being the biggest performance problem, as opening the user's files would result in a lot of File handles on the server. To mitigate, something like varnish would easily solve the problem so long as the vcl file was setup to properly invalidate the cache.

While I think up my next side project, I'll probably continue to tweak BGI and also work on creating a nicer looking front end. My skills are primarily in backend work or hooking up the front end to the backend. Not in making a shiny Web 2.0 website that bedazzles all who gaze upon it. Still, I'll probably try.