Building Content State from Workflow and Audit Logs

Background

For a little while I've been milling over the idea that the state of an object is a result of the history it's been through. For example, you could say that a blog post is the result of multiple iterations of thought, writing, and revising. In order to create something like that, you have a single piece of content having actions applied to it, and this ultimately changes its state. So you think of the following actions that go into making a blog post:

-

Have idea for blog post

-

Write down thoughts

-

Edit and correct typos

-

Read again and look for improvements

-

Improve with more links, references and better wording

-

Publish blog post

This sequence of events could be captured by a few states:

| State | Description |

|---|---|

| Start State | Nothing is done yet |

| Brainstorming Phase | Coming up with an idea for a post |

| Writing | The post is being written |

| Editorial | The post is being reviewed and suggestions made for improving |

| Published | The blog post is done being improved and is out for reading |

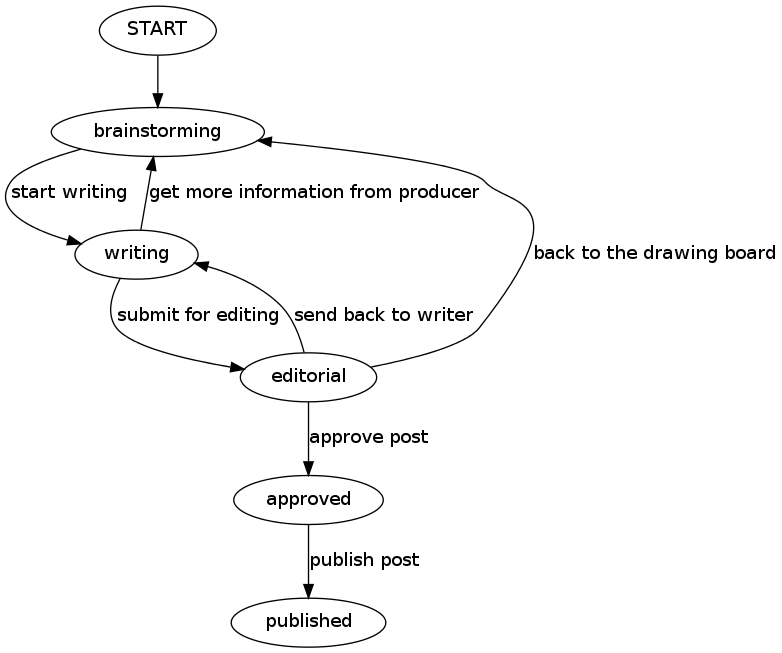

We always have a start state or some kind as a starting point that says that nothing has been done yet for whatever content is being created. Then we move between three main phases: thinking, writing, and reviewing. For a one person team there isn't really a well-defined progression here, but for a team working on a single product there might be very well defined roles for each member. A producer might do most of the brain storming, then pass along their notes to a writer during a meeting. Once the writer has a rough draft, they'll send it to an editorial team. At this point we might loop back saying there needs to be more done before it's ready, which could end up back in either the producer or the writer's court. Either way, it will go through the same set of actions over and over until it finally reaches the published state:

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Brainstorming | Coming up with an idea for a post |

| Start Writing | Someone will start writing |

| Start Editing | Someone will start editing |

| Submit Corrections | Send piece back to writer or producer for more work |

| Publish | The blog post is put out for reading |

As we write out the state's and action's that can be applied to something it is notable that you can begin to see a workflow emerge from this. This leads us to believe that a workflow is the set of actions and states in which content can transition through before it is published. Or generally speaking, before an object has reached an end state with no further actions.

Now let's say that you're not just writing one blog post. But a bunch of them, and your team isn't able to always walk over to each other to check how something is going. At that point, you'll probably end up with something in place to keep track of these things. Maybe basecamp, maybe Jira, maybe something like Salesforce. No matter what you get, you're now in the business of keeping track of not just the content, but what its current state is and where it's supposed to go next. Depending on what you use, you might have a history of events that happened, or you might just have a whole bunch of notes attached to a single object. So long as the management of the content can tell you where to send it next, or why someone added a long essay about some unrelated topic, you're good!

Codifying State

The idea of State is pretty easy to put into code, after all it's just a label right? One thing that helps to know in a workflow is when you can move into a new state. After all, we don't move directly from brainstorming to published! So the idea of a state also includes the idea of a prerequisite. That one state must come before another. The enforcement of this idea is entirely up to the implementation though. For reason's you'll see soon, we'll just leave our model of state simple:

case class State(name: String)

Codifying Action and Workflow

Action is a little more complicated but not by much. An action allows an

object to transition from one state to another, so we'll need a from

and a to field of some kind. On top of that, if we consider actions to

be the links in a directed graph, then they also possess a direction.

For UI purposes, and for our own sanity, we'll also want to include some

human readable information like a name within the model so we can make

sense of any output we're debugging or that we need to show to a user.

sealed trait Direction case object Forward extends Direction case object Backward extends Direction case class Action(from: State, to: State, flow: Direction, name: String)

Using a sealed trait we can ensure that the compiler will know when

we've created an exhaustive match against classes of type Direction.

And we can rest assured that the "direction" of an action will be

represented correctly. Now that we have both States and Actions we

can consider how to model something like the following:

This sums up the scenario we were discussing earlier. In code we might create a list of State's like so:

val start = State("Start")

val brainstorming = State("brainstorming")

val writing = State("writing")

val editorial = State("editorial")

val approved = State("approved")

val published = State("published")

and a set of actions:

val startBrainstorming = Action(start, brainstorming, Forward, "start brainstorming") val startWriting = Action(brainstorming, writing, Forward, "start writing") val getMoreInfo = Action(writing, brainstorming, Backward, "get more information from producer") val sendToEditor = Action(writing, editorial, Forward, "submit for editing") val sendBackToWriter = Action(editorial, writing, Backward, "send back to writer") val backToDrawingBoard = Action(editorial, brainstorming, Backward, "back to the drawing board") val approvePost = Action(editorial, approved, Forward, "approve post") val publishPost = Action(approved, published, Forward, "publish post")

These would become characteristic of our own workflow:

case class Workflow(states: List[State], actions: List[Action])

Tracking content

So now that we have our definition of Workflow as a collection of states and actions, we can move onto how to actually keep track of what state something is in! Essentially, all we need to do is keep track of the actions themselves, allong with any notes about the transition. A log entry than is something like the following:

case class LogEntry(startState: State, endState: State, note: String, flowTaken: Direction, actionTaken: Action)

once we have a list like this, taken in sequential order, we can come up with an algorithm to determine an end state. The algorithm isn't that hard if we have a single chain of events, after all, the last one in the sequence is the last state we were in.

val log: Seq[LogEntry] = ... log.last

But what if your workflow is more complicated and doesn't simply end in an

published state, but also has multiple approval processes and conditions

that need to be satisfied before it's ready? In that case, our log, even

when ordered, will not be as simple as a log.last line of code. Rather,

we'll need to keep track of each "path" through the log to some extent.

Or at least be able to connect entries together and build up a history

of events for each "path".

This isn't too hard considering each LogEntry has both a start and an end

state. We simply need to compare Entry's against the previous and track

all of the last states. This can be done easily with a list of stacks. A

stack is the perfect choice for this since a first in, last out strategy

will allow us to push down as many states as we need, but also get an

answer to what the last state is quickly. A list of stack's allows us to

maintain multiple "paths" in the log by comparing the start state of the

current state to the end state of each element on the top of the stack.

Once the top is figure'd out, we simply push down the element and continue

on from there, the only limitation is that it's first come first serve

for which stack the new entry will be added to should two stacks have

the same end state that matches the new state's beginning.

def determineCurrentState(log: Seq[LogEntry], workflow: Workflow): Set[State] = {

var sequences = List[Stack[LogEntry]](

Stack[LogEntry]()

)

if (log.isEmpty) {

Set[State]()

} else {

for (entry <- log) {

var pushed = false

entry.flowTaken match {

case Forward =>

sequences.map { stack =>

if (stack.isEmpty ||

stack.headOption.map(_.endState) == Some(entry.startState)) {

stack.push(entry)

pushed = true

}

}

if (!pushed) {

val newStack = Stack[LogEntry](entry)

sequences = sequences :+ newStack

}

case Backward =>

sequences.map { stack =>

stack.headOption.map { topEntry =>

if (topEntry.endState == entry.startState && !pushed) {

stack.push(entry)

pushed = true

}

}

}

}

}

}

sequences.map(_.headOption).filter(_.isDefined).map(_.get.endState).toSet

}

The input to the above function is an ordered list, probably pulled from a database somewhere ordered by timestamp or some type of sequencing number. The workflow is passed as a parameter because we could add checks against the workflow to verify that all the state's we're pushing down onto the stacks are allowed to be in that order; but for simplicity the above code doesn't do that. If it did, it'd replace

stack.headOption.map(_.endState) == Some(entry.startState))

with something like:

transitionPermissibleByWorkflow(stach.headOption, entry.startState)

where the flow, start, and end state would all be checked by a helper function.

Once we have the above algorithm we can retrieve a set of States back in a set. This tells us all of the current states for an item and allows us to handle content that has multiple end states. To prove that the code works to yourself, you can checkout the repositories tests here. Of course, knowing a State is handy, but this doesn't tell a user much. After all, someone keeping tabs on an item wants to not only know the state, but also what actions can be taken. This is simple:

def possibleActionsForState(state: State, workflow: Workflow): List[Action] = {

workflow.actions.filter(_.from == state)

}

And if we combine this with our other function:

def possibleActionsForLog(log: Seq[LogEntry], workflow: Workflow): Map[State, List[Action]] = {

determineCurrentState(log, workflow).map(state => state -> possibleActionsForState(state, workflow)).toMap

}

we can now retrieve which actions an item can have performed given a workflow and a log file!

What next?

The next thing to do would be to create some type of simple system or API that allowed this general model to work with your own content. A few ideas pop up to me:

-

Allow input of a workflow via dotfiles or a simplification of

-

Concept of major and minor states, so that the branching that results in multiple end states for a piece of content could be controlled better (branching allowed while in transition from a major to another major).

-

Build a friendly UI to do all the hard work for you! (Building workflows, moving items along, etc).

I know there are systems out there like jBPM, Enhydra, and many more but this is mostly a thought exercise to get the juices flowing. If you implement any workflow structures using this as a base, I want to know! Not just that the code was useful, but also where you had to make updates or changes and why. Happy coding!