CGI with Harp and C - Web front end for the Chat Server

If you haven't read the first post or the previous post you might want to do that before starting this one! If you're looking for the source code for the finished project, you can find that here on github in my repositories. If you want to see and use the finished project you can do so right here.

The Plan

In this post we're going to install Harp, and I'll show you some quick tricks and recipes in making our site look decent. Once the layout is in place we'll connect the front end to the backend with some simple javascript using jquery.

Install Harp

The first we need to do is install harp onto our machines. Harp runs using Node,

so we need to have that installed first. If you're using linux you can use apt-get

or some other package manager to install Node and npm, if you're on windows

then you can download Node from their download page.

Once you have npm installed you can then follow the simple instructions on

harp's quickstart page to install it. To save you the click all you need to do

is run:

npm install -g harp

Note: If you're on windows Node comes with a command prompt you can do to run this, if you're on a *NIX system you can run the above on your terminal (might require sudo).

You've installed harp so now run the following commands to setup our website structure:

mkdir public touch public/chat.js touch public/style.less touch public/_layout.ejs touch public/index.ejs touch harp.json

Some basics in Harp

With that, we have every file we need for our chat server. Let's do a basic "Hello World" for harp now to verify that everything is working properly. First off, we need to define the layout of our page. To quote harp's layout documentation

A Layout is a common template that includes all content except for one main content area. You can think of a Layout as the inverse of a partial.

in other words, your layout defines the parts of your website that don't change from page to page. With harp, you can specify layout's for different pages, or even tell it to not use one at all. By default, Harp will look for a file named _layout with an extension it recognizes (.ejs, .jade, .html).

Now that I've mentioned layout's it bears to say that I should mention partials as

well. We're not using any here for our small site, but if you're going to learn about

Harp, by jove you're going to learn about partials! A partial is similar to a php

script that is include'd into another script. Within a Harp template you can use

the following ejs or jade to bring in another harp file:

<%- partial("_header") %> //in .ejs

!= partial("_header") //in jade

It's also possible to pass parameters to your partials, but you can check out the excellent documentation on partials to read about that. Just becuase you're writing an ejs file does not mean you can't include a jade file. That's one of the beauties of harp, you can mix and match and get what you expect.

Next up on our list of basics, data files! Harp supports two data files, harp.json and _data.json. The file we'll be using is harp.json, which is a global data file accessible from your code anywhere in your ejs or jade files. You cannot access this or any other data object within markdown, html, or any other file besides those two. Since harp.json is a global data sheet, that means _data.json is ... you guessed it, a data file specific to something. Specifically, each directory can have one copy of _data.json with an object of objects stored in the lovely JSON format.

Something you might have noticed about harp filenames is that a few I've mentioned

start off with an underscore. This isn't an accident. Any file you start with _

will be ignored when harp looks to display files. This means that a file _index.html

will not be shown to the user even if they navigate to the URL where you'd expect it.

This doesn't just apply to files though, you can start directory names with one

and harp won't allow public access to anything inside. This isn't to say that harp

itself can't get to them though. In fact, the common usage of the underscore, besides

the _data.json files are to store things like partials, headers, or other

repeatable code that occurs in multiple templates.

We only need one more tool in our arsenal before we can get to the code. The ability

to render content within a layout. This is done by the use of the yield variable.

You can read all the nitty gritty about yield here, but it's actually quite

simple to use and understand. It's a variable that contains the contents of whatever

you're trying to view. If you've navigated to a directory, the index pages contents

will be inserted into the yield variable. Gone to a blog post? That information

you want to share is in the variable. Simple.

With all of that out of the way, this is what our harp.json file looks like:

harp.json

{

"globals" : {

"title" : "Temporary Chat",

"description" : "Chat with whoever is online, yourself, or nobody! A sample chat server made in a tutorial by Ethan Joachim Eldridge",

"chatdomain" : "//www.chat.dev/chat"

}

}

We've defined the global properties of our website. Besides the globals field

all of these properties are arbitrary. You can store whatever you normally store

into a JSON object for use in your site. On my own site I store CDN url's, macro functions,

and even a list of projects. For our server, we've created a sitewide title and description

as well as defined a chatdomain. This domain is going to be a property we use

in our javascripts to tell the front end where to submit requests to.

Note: Readers of the previous post will note that chatdomain is our CGI URL.

Our layout is going to be pretty generic, but we don't need much for this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title><%= title %></title>

<meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<meta name="description" content="<%= description %>" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="/style.css">

</head>

<body>

<%- yield %>

</body>

<script type="text/javascript">

/* Globals for use by the scripts */

window.chatdomain = "<%= chatdomain %>"

</script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/jquery/2.1.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="/chat.js"></script>

</html>

So here we have our first ejs file, if we want to output some variable we wrap it

in <% and %> tags. Once we do this harp will lookup our variable for us and

spit it out (provided it exists). When harp performs a lookup, any data in the

current directory's _data.json file will override anything in the harp.json

global file. This is useful for having a fall back title in your global and then

having specific ones for each page of your site.

In our case, we are spitting out a global javascript variable chatdomain and

attaching it to the window object of the browser. This will allow any of our

javascript files to use the URL stored in harp.json to find out where the CGI

server is. We're also using cloudfare's javascript CDN to get jquery onto our

site without having to download anything to any local environments.

Designing our interface

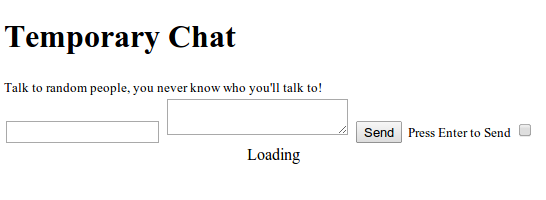

Most people in their twenties know what a chatroom looked like, after all, before we had Facebook and g+ we had AIM, IRC, and chatrooms everywhere. The internet was a wild place of pop-up ads, too many windows open, and being constantly asked for your A/S/L. There's less of that now, but the interface to a chat still typically looks something like this:

We're going to make something similar to this, in that we'll have a main window area to display the current chat going on, and a dialog box of some kind to send messages. Don't worry it will have a much better color scheme and presentation. I promise. That said, let's get some code onto the screen:

index.ejs

<header>

<h1><%= title %></h1>

<small>Talk to random people, you never know who you'll talk to!</small>

</header>

<section>

<form action="/chat/chat.cgi" method="POST">

<input name="u" placeholder="Enter your chat handle">

<sup>

<span name="updates"></span>

</sup>

<button>Send</button>

<label>

<small>Press Enter to Send</small>

<input type="checkbox" name="entersend" />

</label>

<textarea name="m" placeholder="type your message here and press send"></textarea>

</form>

</section>

<section>

<div id="history">

<marquee>Loading</marquee>

<!-- inline becuase pre refuses to listen to us sometimes -->

<pre style="margin: 5px; word-wrap: break-word; overflow-y: auto; max-height: 300px;"></pre>

</div>

</section>

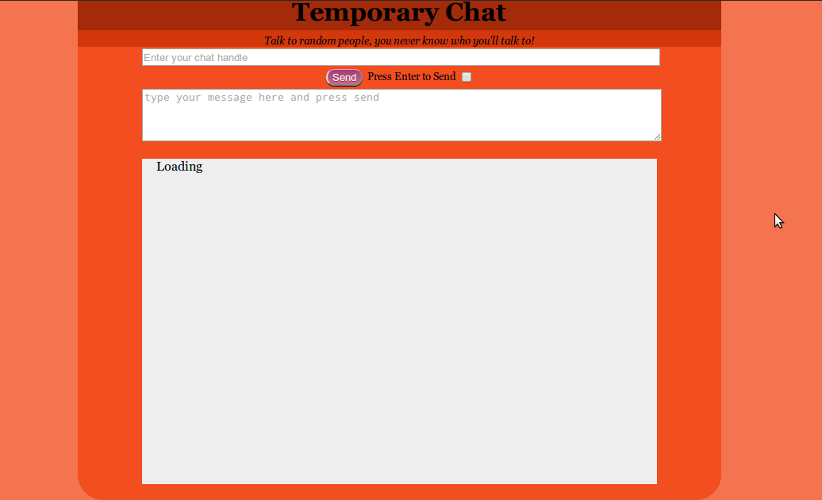

When rendered in a browser we get a bundle of elements on our page:

Yes, we're using a marquee tag. Why not? I like to have some fun with my HTML. And sadly, the blink tag is deprecated. It makes a decent loading animation if you don't want to use something like this to make a nice loading image. Note that our form is posting to our CGI script that will create a message for us. We've also put a send button in place, as well as the option to use enter to send instead of pressing the button. We'll wire this whole thing up after we've made it acceptable to look at.

Styling our site

One of the many reasons I use Harp is for the native less support. I love being able to write my CSS in a hierarchical way. If you haven't used less before, there's no reason to fear! I'm sure you'll understand it with just a single glance at it:

@bgcolor: #F24E20;

html{

font-family: Georgia, Serif;

background-color: lighten(@bgcolor, 10);

}

body{

margin: 0 auto;

text-align: center;

width: 60%;

background-color: @bgcolor;

border-radius: 2em;

header{

width: 100%;

padding: 0;

background-color: darken(@bgcolor, 20);

h1{

padding-bottom: 5px;

margin-top: 0px;

margin-bottom: 0px;

}

small{

display: block;

width: 100%;

padding-top: 5px;

font-style: italic;

background-color: darken(@bgcolor, 10);

}

}

section{

width: 100%;

form{

padding-left: 10%;

width: 80%;

input,textarea{

width: 100%;

display: block;

}

textarea{

min-height: 60px;

}

label{

input{

vertical-align: middle;

display: inline-block;

width: auto;

}

}

}

#history{

min-height: 400px;

background-color: #eee;

width: 80%;

margin-left: 10%;

margin-top: 10px;

margin-bottom: 10px;

padding-bottom: 10px;

div{

min-height: 400px;

display: block;

width: 100%;

overflow: auto;

pre{

text-align: left;

}

}

}

padding-bottom: 10px;

}

}

button {

border-top: 1px solid #f797bf;

background: #d66585;

background: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, from(#9c3e78), to(#d66585));

background: -webkit-linear-gradient(top, #9c3e78, #d66585);

background: -moz-linear-gradient(top, #9c3e78, #d66585);

background: -ms-linear-gradient(top, #9c3e78, #d66585);

background: -o-linear-gradient(top, #9c3e78, #d66585);

-webkit-border-radius: 15px;

-moz-border-radius: 15px;

border-radius: 15px;

-webkit-box-shadow: rgba(0,0,0,1) 0 1px 0;

-moz-box-shadow: rgba(0,0,0,1) 0 1px 0;

box-shadow: rgba(0,0,0,1) 0 1px 0;

text-shadow: rgba(0,0,0,.4) 0 1px 0;

color: white;

text-decoration: none;

vertical-align: middle;

}

button:hover {

cursor: pointer;

border-top-color: #28597a;

background: #28597a;

color: #ccc;

}

button:active {

border-top-color: #1b435e;

background: #1b435e;

}

A couple things, you can pretty much ignore the button css, all of that was

generated here because I'm too lazy to spend a lot of time on a gradient. But

the rest of the code is all mine and yours. The color theme exists to show you

that the darken function of less is very cool. Also, you'll notice that we have

a variable controlling the color scheme of the page. Variables in less begin with

an @ sign, and are declared the same as other CSS properties, like so:

@somevar: sameval;

Another thing to notice is the nesting of elements, this is the hierachical structuring of less that I was talking about. It is very intuitive to follow that the CSS rules apply with the cascade of nesting and only there. Writing the same thing in plain CSS would take a good amount more code and be far less readable. Also, harp minifies your assets for you, so you don't have to go to an outside tool for that either!

Once the above css is in place, the chat screen will now look like this:

Which is far better than a mess of elements on the screen. It's certainly not the most beautiful thing in the world, but it's good enough for this tutorial. We're almost done with our chat server now! We just need to wire the components up!

Note: if you want to run your website with harp and tweak the styles, you

can use harp server from the root of the project to run a local server on port 9000

Connecting Front to Back

The last thing we need to do is handle the javascript talking to our CGI scripts. The high level view of what we're going to do is the following:

-

check that the server is online

-

poll the server for updates

-

create a user handle and keep it

-

send a message

-

recieve all messages

This is not an extensive list of things to do, so let's dive in:

Some setup

chat.js

jQuery( document ).ready(function( $ ) {

var heartbeatURL = window.chatdomain + "/heartbeat.cgi"

var pollURL = window.chatdomain + "/poll.cgi"

var readURL = window.chatdomain + "/read.cgi"

var serverUp = true

})

Note: All javascript code from this point on will be within the .ready's callback function

Remember chat.js? We created this file at the beginning of this tutorial, and now it's time to fill it out. We define a couple convenience URL's so that we can easily change them if the scripts change. This is why we attached the chatdomain to the window object, so we could grab it easily here.

Checking the pulse of the server

To make sure we have a connection to the server we can poll out heartbeat script

and check the initialized field of the returned object. If this is false we know

something is up and we shouldn't allow the user to do anything:

Content-Type: application/JSON

{ "heartbeat" : 1408764565, "initialized" : true }

If we get a response like the above then we know we're still connected and don't

need to disable the chatting functions of the server. We'll be using the serverUp

variable to keep track of whether or not our functions should allow users to chat.

So let's define a couple of utility functions to make our code cleaner later:

var userInputs = 'input,textarea,button'

function modifyInputs(onOrOff){

$(userInputs).prop('disable',onOrOff)

$(userInputs).prop('readonly',onOrOff)

}

function disableInputs(){

modifyInputs(true);

setTimeout(doHeartBeat, 1000)

}

function enableInputs(){

modifyInputs(false)

setTimeout(doServerPoll, 1000)

}

These functions simply toggle the state of user controls for inputting text. Note

that this doesn't stop the button from submitting in all browsers, but we'll be

handling that one in a difference way through our serverUp variable. We're also

calling a couple of functions doHeartbeat and doServerPoll which we'll get to

in a moment.

To check our server we'll send a heartbeat request to our CGI script and check the initialized field of the returned object. If we run into any sort of error on the way, we'll treat it as a failure then keep repeating our heartbeat until something works.

function doHeartBeat(){

$.ajax({

type: "GET",

url: heartbeatURL,

success: function(response){

serverUp = response.initialized

$('marquee').text("Loaded!").blur()

$('marquee').fadeTo("slow",0.0)

$('#history').fadeTo("fast",1.0)

if(serverUp) enableInputs()

else disableInputs()

},

error: function(){

$('marquee').fadeTo("slow",1.0)

$('marquee').text("Could not connect to server,retrying in 1 second").blur()

$('#history').fadeTo("slow",.2)

disableInputs()

}

})

}

There's nothing hard about this code, it simply performs an AJAX request in order to accomplish what we literally just described. A heartbeat server check and an initialization of our Chat server's javascript functionality.

Polling for updates

The next thing we need to do is to begin Polling the server for data. This is accomplished

in the function doServerPoll

var first = true

var lastUpdatedTime = (new Date().getTime()/1000).toFixed(0)

function doServerPoll(){

$.ajax({

type: "GET",

url: pollURL + "?date=" + lastUpdatedTime,

success: function(response){

if( response.updated || first){

first = false

getChatHistory()

}

setTimeout(doServerPoll, 2000)

},

error: function(){

serverUp = false

alert("Connection to Server Lost! Reconnecting...")

doHeartBeat()

}

})

}

This function call is pretty similar to the heartbeat besides we have to handle the

very first call to it. In our first call we need to get the chat history, which we'll

do with the function getChatHistory (not coded yet). We're sending a request to

poll the server if there are any updates to the chat history, and if so, we'll display

them with the chat history function. If we fail we begin checking the heartbeat of

the server again where we'll start the whole process over again. This function, like

doHeartBeat is recursive, calling setTimeout with functions that call itself. Taken

as a whole, the heartbeat and the polling create a timed loop on our page.

Saving the User's handle and persisting it

Our user's need to have names, otherwise we wouldn't be able to tell them apart. Since we have a place to store the user's name all we have to do is monitor that and update a cookie on our users browser whenever neccesary. Because we're saving the information in a cookie we'll be able to remember the user's name whenever they come back to our page.

The cookie format is a simple one, and there exist many javascript wrapper libraries out there that take care of the minutiae of dealing with it for you. But since our use case is so simple we're just going to set it directly.

var cookieName = "userhandle"

function setUserHandle(){

var value = $('input[name=u]').val()

if(value.trim() == "") return;

var date = new Date();

date.setTime(date.getTime()+(365*24*60*60*1000));

var expires = "; expires="+date.toGMTString();

document.cookie = cookieName+"="+value+expires+"; path=/";

}

function readUserHandle() {

var nameEQ = cookieName + "=";

var ca = document.cookie.split(';');

for(var i=0;i < ca.length;i++) {

var c = ca[i];

while (c.charAt(0)==' ') c = c.substring(1,c.length);

if (c.indexOf(nameEQ) == 0) return c.substring(nameEQ.length,c.length);

}

return null;

}

Both of these functions are modified versions of this S.O answer that have been changed to fit into our single cookie use case. With these two utility functions we can automatically set the users name or change it whenever they want. To facilitate this, we'll use jQuery to add an event handler onto the input.

var savedHandle = readUserHandle()

if(savedHandle != null){

$('input[name=u]').val(savedHandle)

}

$('input[name=u]').on('keyup',setUserHandle)

$('input[name=u]').on('change',setUserHandle)

Whenever a user presses a key or moves their focus outside of the user input box we'll set the handle cookie. In addition, we come to the first line of code that aren't just function calls! When the page loads we'll grab the cookie of the user and if it exists we'll set the input to that value. In this way, we provide the user with the pleasant experience of not having to enter their handle everytime.

Sending the server a message

While you can post the form right now and it will submit, it's not very helpful to send the user away from the screen they're on for a live chat experience. So we need to override the handlers on the form itself to prevent the page from changing, this is easily done like so:

$('form').submit(function(evt){

evt.preventDefault()

if(!serverUp){

alert("The Server is not available right now. Please wait while we establish your connection")

return false

}

/* Some simple validation */

if( $('input[name=u]').val().trim() == "" ){

alert("You must enter a username!")

return false

}

if( $('input[name=u]').val().trim().length > 20 ){

alert("usernames must be less than 20 characters")

return false

}

if( $('textarea').val().trim() == "" ){

alert("Please enter a message before sending")

return false

}

var data = $(this).serialize()

var url = $(this).attr('action')

var method = $(this).attr('method')

$(this).fadeTo("slow",0.5)

$.ajax({

type: method,

data: data,

url: url,

context: this,

success: function(response){

var updates = $(this).find('span[name=updates]')

updates.text(response.message)

setTimeout(function(){

updates.text("")

}, 500)

$(this).find('textarea').val("")

$(this).fadeTo("slow",1.0)

$(this).find('textarea').focus()

},

error: function(){

var updates = $(this).find('span[name=updates]')

updates.text("There was an error in contacting the server, please hold.")

setTimeout(function(){

updates.text("")

}, 3000)

$(this).fadeTo("slow",1.0)

serverUp = false

doHeartBeat()

}

})

return false

})

Note that the only reason this function is so much code is because we validate that we

actually submitting something to the server before we send it. Even though we

do validation on the server itself, it's still best practices to validate everywhere.

Within the success/error callbacks of the $.ajax method we're using the span

tag inside. If we fail we'll update the span tags to show a message to the user

for a short period of time.

The only thing left to do as far as sending messages go, is to make it possible to send a chat message by pressing the enter key. We can do this by monitoring the clicked state of the checkbox, and updating a boolean variable within the javascript that is used by another listener on the textarea.

var enterToSend = false

$('input[name=entersend]').click(function(evt){

entersend = this.checked

})

$('textarea[name=m]').on('keydown',function(evt){

if(entersend){

if (event.which == 13 || event.keyCode == 13) {

$('form').submit()

}

}

})

We use both event.which and event.keyCode becuase some browsers don't support

keyCode. With this in place we can finish up our chat server by showing what

we've been submitting to the user.

Reading the chat history

Believe it or not, this is extremely easy to do. Our last, but most important

function to write is getChatHistory, called from our first polling to the

server, it's what loads the current chat into the user's view and lets them

know they're online. It's a simple ajax call and one important assignment to

lastUpdatedTime:

function scrollFix(){

var elem = $('#history pre')[0]

elem.scrollTop = elem.scrollHeight

}

function getChatHistory(){

$.ajax({

url: readURL,

method: "GET",

error: function(){

$('#history pre').text("Could not load chat history!")

doHeartBeat()

},

success: function(response){

/* The response is plain/text */

$('#history pre').text(response)

scrollFix()

lastUpdatedTime = (new Date().getTime()/1000).toFixed(0)

}

})

}

By setting lastUpdatedTime to when we last updated our chat history the polling

we do in doServerPoll is able to send us any updates that we haven't recieved

yet. If we fail, we ask to perform the heartbeat to check if the server is alive

and we let the user know we coudn't load their text. Also, we move the view of the

history down by calling our scrollFix function.

Finishing up

With that, we're finished up. You can see and use the final product right here and chat with me or anyone else who's online. The files are temporary so they'll be cleared out whenever I reboot my server and also whenever I run a cronjob to remove the chat file. If you find any bugs or errors please let me know and I'll get onto fixing it. Have fun and I hope you learned something!