Day 8: DSU! Gesundheit! ↩

Now that we're in the latter half of the challenge, the problems increase in difficultly. And for me, that takes the form of algorithms and data structures that I never learned about in school. It's not hard to read a wikipedia page and implement something, but it is hard to recognize that you don't know something you don't know. And that, and the subtle (to me) wording of the problem, is what made Day 8 much harder than any of the previous days I noted in my last write up.

The problem's input was a set of 3 dimensional points that were easy enough to parse. Given those lists of points, the problem then proceeded to explain that our goal was to connect some amount of points in order to get electricity going through the circuits based on some criteria and then provide the product of the three largest circuits that were created.

I got part of the criteria at first blush. Which, is pretty good considering it was 6 in the morning. I, for the 3rd time this year, didn't stay up until midnight to start the problem right away 1. Which, was probably a good thing considering this would definitely have frustrated and nerd sniped me deep into the night. On the other hand, I might have had better reading comprehension at midnight than at the point in the day when my eyes are quite bleary.

Oh the gripping hand, regardless of my eyesight, I still didn't actually know the right algorithm for the job when it came to "connect all the nodes in shortest distance order and skip nodes that are already connected". Rather, I misread it as "compute the shortest distance between all pairs and traverse the resulting set to find path length."

These are. Well. They're not the same thing. Or, well, maybe they sorta are. But I definitely wasn't doing it right. To my credit, the code I wrote did traverse the data! The parse was easy enough, if not full of expectations of greatness:

type PointType = i128;

type Tuple3 = (PointType, PointType, PointType);

let num_connections = 1000;

let points: Vec<Tuple3> = raw_data.lines().take_while(|line| !line.is_empty()).map(|line| {

let mut iter = line.split(",");

(

iter.next().expect("Option not defined x").parse::<PointType>().expect("Could not parse number x"),

iter.next().expect("Option not defined y").parse::<PointType>().expect("Could not parse number y"),

iter.next().expect("Option not defined z").parse::<PointType>().expect("Could not parse number z")

)

}).collect();

What? You expected me to not make a joke about expect? Well your expectations

were wrong, and I expect you might be getting tired of expecting the next use of the word.

So. With my points in hand, I set about figuring out the shortest distances and which point

was closest to another:

let mut circuits: HashMap<Tuple3, HashSet<Tuple3>> = HashMap::new();

for point in &points {

let mut shortest_distance = PointType::MAX;

let mut point_with_shortest_distance = point;

for other_point in &points {

// We don't care about ourselves.

if point == other_point {

continue;

}

let d = euclidean_distance_squared(point, other_point);

let connections = circuits.entry(*point).or_default();

let not_in_circuit_yet = !connections.contains(other_point);

if shortest_distance > d && not_in_circuit_yet {

shortest_distance = d;

point_with_shortest_distance = other_point;

}

}

if point != point_with_shortest_distance {

let connections = circuits.entry(*point).or_default();

connections.insert(*point_with_shortest_distance);

}

}

Feeling like I was getting somewhere, I confidently put finger to keyboard and

fought the borrow checker demon for 21 minutes. I left with a few bruises though,

I really wanted to use or_default but lifetimes and the fact that I

was storing references to tuples, rather than the tuples themselves, left me bleeding

with the match arms of fury laying my code out into the usual nested fish shape:

// We now have 1 connection between each item to its shortest distance neighbor

// so now we need to traverse each circuit and compute the three largest circuit

let mut circuit_sizes = vec!();

for (start, _) in &circuits {

let mut seen: HashSet<&Tuple3> = HashSet::new();

let mut path = vec![start];

let mut size = 1;

while let Some(point) = path.pop() {

seen.insert(point);

match circuits.get(point) {

Some(connections) => {

for c in connections.iter() {

if !seen.contains(c) {

println!("{:?} -> {:?}", point, c);

size += 1;

path.push(&c);

}

}

},

None => ()

};

}

circuit_sizes.push(size);

}

The depth first search I was doing didn't work. Well. I mean, it worked

but it didn't work. The result of taking a single path through

from one point to another, especially in something like a hash set, gave me

different traversals each time until I moved the seen declaration

inside of the outer for loop. For some reason I left it out at first. Which,

I probably did due to the fact that the word problem implied 2 we should

track nodes that were already used up and skip them.

Despite stabalizing the answer, it was still wrong. I had 50 minutes until work started and hadn't done my morning routine yet, so I committed and decided to circle back later. Giving up that I probably wouldn't be beating my co-worker in the AoC race today.

After work I decided to use Large Language Models for what they were, potentially, intended to be used for. Processing language. Just because my reading comprehension was low doesn't mean that I can't pretend I'm Rimuru from the funny Slime show. He uses Raphael for all she's worth after all.

Stop judging. It's not like I went to the robot and pasted in the problem and told it to give a code solution. No, I had much more noble ambitions! First, I had it make sure I wasn't screwing up the traversal somehow in a subtle way. I mean, I was getting so close I thought. So, I provided it with the rough idea of what I was doing, the code I had written so far, and then a couple paragraphs of the word problem text.

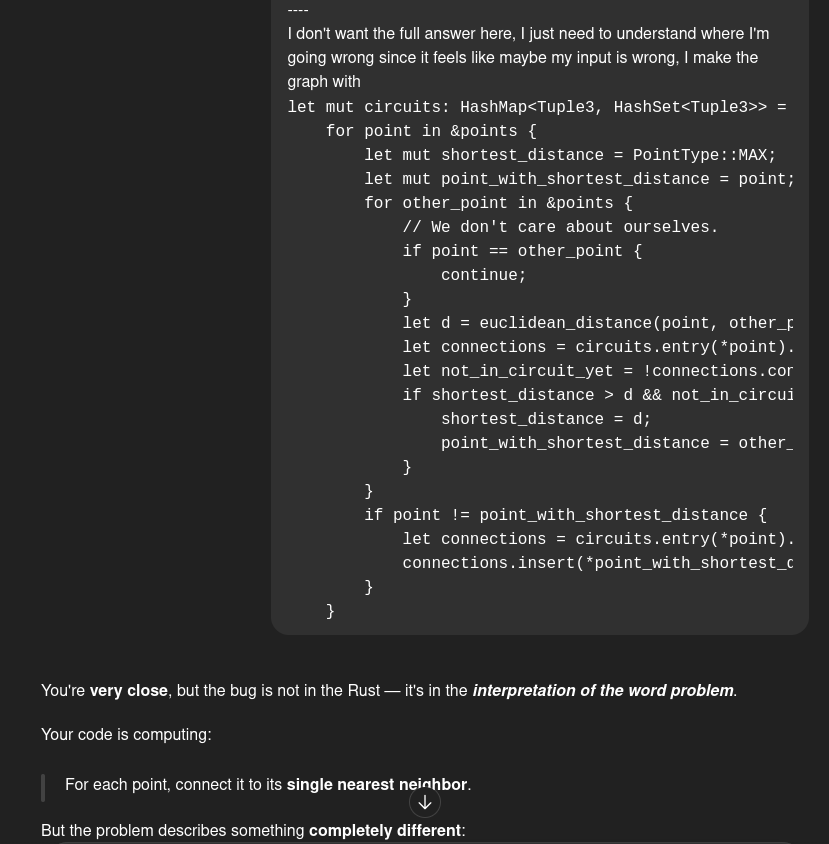

I didn't really trust myself to paraphrase a word problem I was obviously misterpretting. So, I copied over what felt relevant, showed it how I was constructing my hash map and waited a moment:

Oh good. Well, I was at least correct that I had misinterpretted the problem! The robo buddy proceeded to tell me that I was doing a local solution rather than a global one. My code was creating 20 edges for 20 nodes. Pairwise! But the word problem, was actually asking me to connect N edges within the list of pairs.

To me this was pretty subtle. One of those, re-read the problem, tilt your head, and go "eeehhh, guess you could read it that way" and stubbornly cling to the idea that you actually know how to use the electrical furnace between your ears properly. Once I put my ego aside though, the fact that I was just connecting points to their closest neighbor and maybe a couple others was clear enough. A hint the explanation had also tried to steer me to this, and I had ignored it because I was excited to write DFS.

After making the ten shortest connections, there are 11 circuits

I had 20 edges after my calculations. At least. Not the ten that it mentioned. So my code wasn't following what it wanted, and so, off it goes. Despite the fact that I had included "don't give me the answer" in the prompt. It still provided a walkthrough of rough pseudo code and whatnot I couldn't help but skim over. I'm a curious guy, you put code in front of me and I'm going to start to read it.

Or at very least, skim the headers, and when I did the important need-to-know word popped out: Kruskal.

Any time you're given a random person's last name, you can believe that there's an algorithm you probably need to know. A lot of advent of code stuff tends to devolve into graph theory. Which is unfortunate, as my professor had a death in the family and my class was gipped of a whole chunk of curriculum because of it. We learned Djikstra, but I honestly don't remember ever hearing about a "minimum spanning forest" before.

But hey! Always time to learn something new! And in this case, the wikipedia directed me to disjoint union sets and thus, we had a fun little data structure to use:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct DSU {

parent: Vec<usize>,

size: Vec<usize>,

}

impl DSU {

fn new(n: usize) -> Self {

DSU {

parent: (0..n).collect(),

size: vec![1; n],

}

}

fn find(&mut self, x: usize) -> usize {

if self.parent[x] != x {

self.parent[x] = self.find(self.parent[x]);

}

self.parent[x]

}

fn union(&mut self, a: usize, b: usize) -> bool {

let mut a = self.find(a);

let mut b = self.find(b);

if a == b {

return false;

}

// union by size

if self.size[a] < self.size[b] {

std::mem::swap(&mut a, &mut b);

}

self.parent[b] = a;

self.size[a] += self.size[b];

true

}

}

What is this thing? The DSU

is a cool way to represent sets. The neat thing about them is that they're self-optimizing. Every

time we perform a find operation, we end up compressing the path down a bit by making

the list of who's who's parents all point to their root. So, let's say that you had a list of indices

like this:

Parents: [ 0, 0, 1, 2, 3 ] index: [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 ]

Where these are the self.parent values for a small set of edges. The 0th item here

points to itself, indicating that it's the root. That's also the recursive base case. Now,

if I were to call find(3), then we'd slowly update the parent list and on

each iteration we'd set the parent to become the result of the previous find. This will

descene all the way from 3 to 0, then return all the way back, setting the parent along

the way so that you end up with

[ 0, 0, 0, 0, 3]

Where everything from index 3 has been followed and "compressed" down to point to the root. So the next time you ask the DSU "hey, what's the root of index 2?" it doesn't recurse, or curse you out, instead, it just happily says: "Oh that would be 0!" instantly. It's pretty awesome honestly, and a neat side effect of this is that the union operation becomes quick the more you use it.

The union function in the DSU does what you expect it to. If you tell it to

create a union between point a and b it does! But only if it

hasn't done it already. The wikipedia article makes a few notes about different styles of

union-ing and how it impacts the data. But most importantly, it notes that union by size

is a thing. And what are we computing for our problem? Sizes of the circuits, aka sizes of

the sets. It certainly feels like tracking that size information will be helpful!

And it was. As was falling to the natural desire to return a boolean from the operation indicating if the union actually happened or not. This made part two super easy. But, before I get ahead of myself, once you have the DSU the code to solve part 1 became another test of reading comprehension and not forgetting to avoid hardcoding in the example problems limits. Consider the code:

let mut dsu = DSU::new(points.len());

let mut attempts = 0;

for (_, i, j) in edges {

if attempts == num_connections {

break;

}

attempts += 1;

dsu.union(i, j);

}

As you can see, after num_connections we stop. As per usual when doing advent of

code, I followed the example problem first and made sure that I was able to produce the proper

result. This means that num_connections was 10. Running the code on the real input

with this set gives you the wrong answer, and a very confused session of staring at code wondering

what's wrong. Of course, once figured out it's easy to tweak! But then, forgetting to untweak

it while working on part 2 provided me with a rake to the face:

thread 'main' panicked at src/main.rs:77:34: index out of bounds: the len is 1 but the index is 1 note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtrace

If it's not one thing, it's the other. But either way, part 1 was completed after a reading of the proper wikipedia page and I had been told that part 2 "had hands". So I braced myself.

And then seven minutes later committed my solution after getting my second gold star.

Part 2 asked us to multiple the two X values of the points that resulted in the circuit becoming fully connected. Remember how I said it's useful when an insertion/merging/union function returns a result about whether it worked or not? That made this trivially easy:

let mut dsu = DSU::new(points.len());

let mut merges = 0;

let mut final_merge: Option<(Tuple3, Tuple3)> = None;

for (_, i, j) in edges {

let merged = dsu.union(i, j);

if merged {

merges += 1;

}

if merges == points.len() -1 {

final_merge = Some((points[i], points[j]));

break;

}

}

let final_merge = final_merge.expect("Didnt compute final merge?");

println!("final merge X {:?}", final_merge.0.0 * final_merge.1.0);

I suppose I could have just computed the result without moving the value out

with an Option but eh. I like having that last bit of "this is

how to get the result" type code out on its own. Just feels nicer. If you've

got 2 nodes to connect, then if you were to count how many merges it takes to

do, you'd only have 1. Connecting 3 nodes together? You'll need to union 2 times.

See the pattern? And so, we can easily tell that we've hit on the last merge

of the unconnected data when we've seen length(points)-1 merges completed.

While I got stumped, thought about it all day at work, and didn't beat my coworker on the leaderboard at all, at least I learned something new! Last year I got introduced to how cool Tries can be during advent of code, and this year it seems that DSUs are the neat new thing I found out about! Now, do I expect a DSU to somehow prompt an excursion into trie-ing to save memory for my editor plugin? Not really. But who knows, we'll see what it brings later on in life!

Day 9 - Geometry is pain ↩

I suppose, it's hard to keep your eye on the future when the past keeps tripping you up. And by that, I mean the fact that I'm still very very bad at remembering things that I'm pretty sure were taught back in middle and high school. Or at least that's the thought that comes to mind when days like Day 9 happen. This was very similar in spirit to Day 13 of last year for me.

The problem's part one was extremely simple, deceptively so. I set myself up with a parse of the input, which was a list of points representing "red tiles", in about 5 minutes between reading the problem and throwing together the now, as per usual, parse of the data:

type ResultType = i64;

fn p1(raw_data: &str) -> ResultType {

let tiles: Vec<(ResultType, ResultType)> = raw_data

.lines()

.take_while(|line| !line.is_empty())

.map(|line| {

let mut xy = line.split(",");

(

xy.next().expect("no digit x").parse().expect("bad number x"),

xy.next().expect("no digit y").parse().expect("bad number y")

)

})

.collect();

within 10 minutes after, I read through the data, ran into an off by one error, and solved the first part of the problem. Brute force was basically the only thing you could do with this, as the question was simple: given these points, if you make rectangles with each pair of points as the opposing corners, which has the largest area?

let mut areas = vec![];

for p1 in tiles.iter() {

for p2 in tiles.iter() {

if p1 == p2 {

continue;

}

let area = (1 + (p1.0 - p2.0).abs()) * (1 + (p1.1 - p2.1).abs());

areas.push(area);

}

}

areas.sort();

*areas.iter().rev().take(1).next().expect("No answer")

}

You can probably tell that the 1 + area of the code (haha, area) was where

that off by one issue happened. We're working with an integer grid, so if you have a

rectangle between two points on the same line, like this:

..... .XXX. .....

Then we actually care about the area represented by the tiles not the numeric

area you'd compute with a normal area function. So, this one has an area of 3, since it's

3 x 1 from (1 + (1 - 1).abs()) * (1 + (3 - 1).abs()), you'd

get an unhelpful non-integral number if you actually computed (1 - 3).abs() * (1 - 1)

which would just give you 0.

Easy! We're only 15 minutes into the day, I'll totally get to bed early and get a good night's sleep. Right?

No. Not at all. 30 minutes later I had read through the second part of the problem, thought about a few different potential things to do, and already understand that I was going to be in trouble. The problem described drawing in some 'green tiles' between each red tile. Easy!

let mut green_tiles = HashSet::new();

let n = red_tiles.len();

// don't forget the edges.

for i in 0..n {

let first = red_tiles[i];

let second = if i + 1 != n {

red_tiles[i + 1]

} else {

red_tiles[0]

};

// there is a green STRAIGHT line between these two points.

let bx = first.0.min(second.0);

let bxMax = first.0.max(second.0);

let by = first.1.min(second.1);

let byMax = first.1.max(second.1);

for x in bx..=bxMax {

for y in by..=byMax {

// we technically count the red tiles as green, but that doesn't matter.

green_tiles.insert((x, y));

}

}

}

But then, the problem said that all of the tiles inside the loop of green and red tiles are also green. Or, in other words, the shape is filled in. This immediately made me think Flood Fill!. I swiftly realized that I had two problems. One, was that in order to flood fill, we need to actually know a point that's already inside the shape we've drawn with the tiles.

I struggled with trying to come up with a way to do that reliably in a general sense, but at the end of the day, I attempted to render the grid. Which failed, it was too big and even when I did print off a few lines, it was not particularly conducive to being viewed in an editor. Sublime Text can open it fine, but word wrapped or not, the shape of the thing is hard to view. After agonizing over it for well over an hour, I just tossed a check into the code to take the minimum point and maximum point across the whole set of points, then watch for if we flooded out of that after choosing a point and starting the usual suspect:

// arbitrary point taken by taking 1 point and shifting around based on its neighbor

let start_point = (97713,51514);

let mut queue = Vec::new();

queue.push(start_point);

while let Some(tile) = queue.pop() {

for dx in -1..=1 {

for dy in -1..=1 {

let new_tile = (tile.0 + dx, tile.1 + dy);

if new_tile.0 < min_x || new_tile.0 > max_x {

println!("bad seed");

continue;

}

if new_tile.1 < min_y || new_tile.1 > max_y {

println!("bad seed");

continue;

}

if green_tiles.contains(&new_tile) {

continue;

} else {

green_tiles.insert(new_tile.clone());

queue.push(new_tile.clone());

}

}

}

}

When the terminal sat quiet, not printing anything off about going out, but also not terminating. I checked out how far along the code was getting. It was able to flood and create the green_tiles! Used plenty of memory, but, it did generate all the green tiles. The issue was that once I had those green tiles, we had to check against them to find the actual answer to the question.

What's the largest area of the rectangle that is still completely green/red?

let mut areas = vec![];

for p1 in red_tiles.iter() {

for p2 in red_tiles.iter() {

if p1 == p2 {

continue;

}

let area = (1 + (p1.0 - p2.0).abs()) * (1 + (p1.1 - p2.1).abs());

areas.push((area, p1, p2));

}

}

areas.sort_by_key(|(a, _, _)| *a);

// Walk backward from the largest area to the smallest

let mut largest_area = 0;

for (area, p1, p2) in areas.iter().rev() {

let mut is_green = true;

let bx = p1.0.min(p2.0);

let bxMax = p1.0.max(p2.0);

let by = p1.1.min(p2.1);

let byMax = p1.1.max(p2.1);

for x in bx..=bxMax {

for y in by..=byMax {

// we technically count the red tiles as green, but that doesn't matter.

if !green_tiles.contains(&(x, y)) {

is_green = false;

break;

}

}

if !is_green {

break;

}

}

if is_green && *area > largest_area {

largest_area = *area;

}

}

My traversal worked. The braindead logic to just check if every tile in an area was in the hash was correct. But only, technically correct. I knew it was inefficent, so I went ahead and started up the program and opened bottom and watched my memory slowly climb as I layed in bed and looked at the clock.

2:27am.

Laying in bed, listening to the Bocchi the Rock soundtrack, I closed my eyes and kept thinking about it. How long would it take for the code to run? Should I even bother? It was only using one my cpu cores, I suppose I could try to parallelize things, but meh, it doesn't seem like a good idea. Is there a different way to figure it out?

If I'm running out of memory because of the hashset tracking every single point. Then just don't do that? So, how, given a point, do you tell that it's within a polygon? This led me down the rabbit hole, rather than tracking the points I attempted to just cast out a ray from the point down to one of the axis using the idea that if I hit a green wall along the way, then that meant I was inside of the shape.

Except, how the heck do you make sure you deal with the 1 tile tall bits that can exist? I went back and forth on that for a while, struggling to visualize the way the walls could appear in whatever arbitrary pixel-y shape that had appeared. Is it really okay to ignore the "filled in" part? Is it enough to be "in" the shape already?

3:20am.

fn point_in_poly(x: ResultType, y: ResultType, poly: &Vec<(ResultType, ResultType)>) -> bool {

let mut crossings = 0;

let n = poly.len();

for i in 0..n {

let (x1, y1) = poly[i];

let (x2, y2) = poly[(i+1) % n];

// Check if ray crosses the edge

let intersects = ((y1 > y) != (y2 > y)) &&

(x < (x2 - x1) * (y - y1) / (y2 - y1) + x1);

if intersects {

crossings += 1;

}

}

crossings % 2 == 1

}

I tried running this across all the tiles again and watched the CPU spike and spin. Hm. Nope. No dice. Time to sleep, I've got work in the morning after all.

7:00am.

Alright, off we go. I caught up on IRC and happened to see someone talking about their Haskell solution. I was stumped, and so a hint could be nice. Geometry, and the fact that I was now looking at random websites with "research" in the path suggested to me that I needed help. And, Haskell is a language I don't know. So, it's sort of like getting an obfusuated clue!

The vague idea to check out intersections and adjencies across the polygon in this vague way that confused my head seemed like a good thing to try to tackle. Even if I had the haskell code, composing it to rust was still something to feel good about. So, even if I feel bad about not figuring out the solution, or trying to translate someone's research notes on PNPOLY, I could still write the code out and do my best to understand it at least.

As nine o'clock rolled around, I went ahead and ran a port of the haskell code and confirmed that it got me a star. So the idea was solid! Knowing that I wasn't about to go down the wrong path, I picked up a shovel and started digging. I ended up asking an AI to generate unit tests for me to validate against for the different parts one needed to implement the algorithm.

I like unit tests, they're helpful guideposts! And when you're struggling and feeling like you're the dumbest person on the planet because you can't visualize an edge and some polygons floating around, it's helpful to have small milestones to work towards. So, I ended up with some function signatures

/// https://stackoverflow.com/questions/3235385/given-a-bounding-box-and-a-line-two-points-determine-if-the-line-intersects-t

pub fn adjacent_edge_intersects(

rect: ((ResultType,ResultType),(ResultType,ResultType)),

edge: ((ResultType,ResultType),(ResultType,ResultType)),

) -> bool {

...

}

pub fn point_in_poly(x: ResultType, y: ResultType, poly: &[(ResultType,ResultType)]) -> bool {

...

}

/// plus 1 to deal with the grid nature of things. a single line still has area of 1

pub fn rectangle_area(p1: (ResultType,ResultType), p2: (ResultType,ResultType)) -> ResultType {

(1 + (p1.0 - p2.0).abs()) * (1 + (p1.1 - p2.1).abs())

}

The hardest one to get right was the first one. "Adjacent edge intersect", a terrible name. But one which is maybe more clear from the test cases:

#[test]

fn test_adj_edge_does_not_intersect_valid_rect() {

let rect = ((2,3),(9,5));

let edge = ((7,1),(11,1)); // horizontal above rectangle

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn test_adj_edge_intersects_invalid_rect() {

let rect = ((2,3),(9,5));

let edge = ((8,2),(8,6));

// vertical line at x=8, spanning y=2..6 → passes through interior

assert!(adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_horizontal_crosses_rect_interior() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((0, 4), (20, 4)); // passes straight through rectangle interior

assert!(adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_horizontal_outside_rect_does_not_intersect() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((0, 2), (20, 2)); // entirely below

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_horizontal_touching_top_boundary_does_not_intersect() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((0, 3), (20, 3)); // exactly on top boundary

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_horizontal_touching_bottom_boundary_does_not_intersect() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((0, 5), (20, 5)); // exactly on bottom boundary

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_vertical_crosses_rect_interior() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((4, 0), (4, 20)); // passes straight through rectangle interior

assert!(adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_vertical_outside_rect_does_not_intersect() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((10, 0), (10, 20)); // entirely to the right

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_vertical_touching_left_boundary_does_not_intersect() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((2, 0), (2, 20)); // exactly on left boundary

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

#[test]

fn edge_vertical_touching_right_boundary_does_not_intersect() {

let rect = ((2, 3), (9, 5));

let edge = ((9, 0), (9, 20)); // exactly on right boundary

assert!(!adjacent_edge_intersects(rect, edge));

}

With these and some tests for correct behavior, I got down to business after work and after a half hour I had a working implementation of the whole not-on-the-boundary-and-doesn't-intersect algorithm:

fn largest_valid_rectangle(red_tiles: &[(ResultType,ResultType)]) -> ResultType {

let mut max_area = 0;

for p1 in red_tiles {

for p2 in red_tiles {

if p1 == p2 {

continue;

}

let left = min(p1.0, p2.0);

let right = max(p1.0, p2.0);

let top = min(p1.1, p2.1);

let bottom = max(p1.1, p2.1);

// are the corners inside of the polygon?

if !(

point_in_poly(left, top, red_tiles) &&

point_in_poly(left, bottom, red_tiles) &&

point_in_poly(right, top, red_tiles) &&

point_in_poly(right, bottom, red_tiles)

) {

continue;

}

// do we intersect with any of the edges of the shape?

let mut blocked = false;

for i in 0..red_tiles.len() {

let a = red_tiles[i];

let b = red_tiles[(i+1) % red_tiles.len()];

if adjacent_edge_intersects(( (left, top), (right, bottom) ), (a,b)) {

blocked = true;

break;

}

}

if blocked {

continue;

}

let area = (1 + (p1.0 - p2.0).abs()) * (1 + (p1.1 - p2.1).abs());

if area > max_area {

max_area = area;

}

}

}

max_area

}

With that Day 9 was complete. But I wasn't particularly happy about it. That was two days in a row that I had needed a hint. I guess we are in the latter half of Advent of Code now, so the problems are expected to become more difficult. But it still sort of stings. I feel like I'm partially shaking off the dust on my rust, but even if you try to get a local AI model in tutor mode, they still sometimes just dump a solution on you without asking. Which ruins some of the fun and then you don't get that sort of frictional learning that really makes things stick.

Of course, life is about balance. I shouldn't be staying up 'til nearly 4am on a workday. That excitement of trial and error, of going to bed for a moment, only to jump up again as that "wait, what if I just try THIS!?" it's just so fun. I think that using the unit tests as a guide helped a bit after that welp, I've seen a haskell solution, guess I'll just port it as my puzzle work helped me recover a little bit on that. But, eh, I know I'd still feel better if I did it all myself.

Anyway. Before I spiral like I did when I struggled with annoying bounding box and obstacle collision issues with making a breakout clone, it's time to move on to the next day! Surely, it won't be another day of terrifying math and sadness!

Day 10 - Terrifying math and sadness ↩

Day ten began on time. Midnight hit, I init, and off to parse we go! Kinda, I was a little distracted and so 13 minutes later I only had a unit test setup because I had to decide how to represent the data in a way that would make sense, and then we run into the world of parsing strings in rust, which is never… it's just not great. Anywho, the test:

fn test_parse() {

let (m, buttons, joltages) = parse("[.##.] (3) (1,3) (2) (2,3) (0,2) (0,1) {3,5,4,7}");

assert_eq!(m, vec![0,1,1,0]);

assert_eq!(buttons, vec![

vec![0,0,0,1],

vec![0,1,0,1],

vec![0,0,1,0],

vec![0,0,1,1],

vec![1,0,1,0],

vec![1,1,0,0]

]);

assert_eq!(joltages, vec![3,5,4,7])

}

As you can see, I chose to represent the data with a bunch of vectors. The input is the desired state of the lights on a machine, the buttons which can toggle said lights on and off, and then some "joltage" values that the word problem ominously stated

Because none of the machines are running, the joltage requirements are irrelevant and can be safely ignored.

So we know part 2 will definitely involve the joltage in some fashion. But, for another hour or so we can remain in blissful ignorance. It wasn't hard to convert the example problem into a series of unit tests before I began. The problem itself wasn't too bad to think about. It's an easy brute force question:

Given an initial state of nothing on, press the buttons to toggle the lights to get to the goal state. The button like (0) would mean it toggles the first light. (1,3) toggles both the 2nd and 4th light. And we can press the buttons as many times as we'd like. But of course, the actual output of the problem is the minimum number of presses to get to the goal.

I continued my slow and steady approach with unit tests, adding in a couple helper methods

to try to express myself in an easy to read way to, hopefully, avoid confusion later. I had

parsed the input like (0) to be [1,0,0,0], that way I

didn't have to compute or hop around later, just a pseudo bitset without having to think about

the minutia of << or >>, and with a couple helpers,

I can easily apply a click to a "machine" which, as you'd guess, is also a list of 1s and 0s.

fn apply_button(mut machine: Vec<u8>, button_click: Vec<usize>) -> Vec<u8> {

for i in 0..machine.len() {

machine[i] = machine[i] ^ button_click[i] as u8;

}

machine

}

fn machine_done(machine: &Vec<u8>, goal: &Vec<u8>) -> bool {

for i in 0..machine.len() {

if machine[i] != goal[i] {

return false

}

}

true

}

Converting this into a breadth first search across the potential changes is the easy. We can just keep track of the program state, apply all the possible buttons, and BFS away

fn fewest_presses(goal: Vec<u8>, buttons: Vec<Vec<u8>>) -> usize {

let n = goal.len();

let start = vec![0u8; n];

if start == goal {

return 0;

}

// We just BFS to explore all options brute force for now

let mut q = VecDeque::new();

q.push_back((start.clone(), 0usize));

let mut visited = HashSet::new();

visited.insert(start);

while let Some((state, dist)) = q.pop_front() {

for btn in &buttons {

let next = apply_button(state.clone(), btn);

if !visited.contains(&next) {

if machine_done(&next, &goal) {

return dist + 1;

}

visited.insert(next.clone());

q.push_back((next, dist + 1));

}

}

}

// arbitrary nonsense.

usize::MAX

}

Since the problem description didn't say anything about what to do when a machine can't be solved, I (correctly) assumed that every machine was possible to solve. What I didn't do correctly though, and what occupied the next 40 minutes until I solved part 1, was realizing that my parsing of the data was incorrect. One stupid trailing ) later, and at 1:32am I had a gold star.

I told myself I should go to bed and do part 2 tomorrow, since it was getting late and I had work the next day.

fn apply_joltage(mut joltage: Vec<usize>, button_click: &[u8]) -> Vec<usize> {

for i in 0..joltage.len() {

if button_click[i] == 1 {

joltage[i] += 1;

}

}

joltage

}

Since part 2, as expected, involved the joltage, I made a helper to apply it. The buttons operate the same way as they do on the lights, but instead of toggling, they just increase the amount of joltage being sent for a particular battery or whatever this thing runs on. Perhaps because it was late at night, I misunderstood and missed the very important sentence:

Each machine needs to be configured to exactly the specified joltage levels to function properly. Below the buttons on each machine is a big lever that you can use to switch the buttons from configuring the indicator lights to increasing the joltage levels.

Looking at the word problem as I write this, it seems a lot of people missed this, and the following parenthetical was added so that all of us sharing the same 3 collective brain cells wouldn't waste their time with trying to solve both the ligthts and the joltage at the same time:

(Ignore the indicator light diagrams.)

As you may have guessed, I did not ignore this at first and so I updated my BFS to try to search that space:

q.push_back(((start.clone(), start_joltage.clone()), 0usize)); let mut visited = HashSet::new(); visited.insert((start, start_joltage)); ...

It took me about a half hour to rub my two neurons together and realize my mistake. Even with that out of the way though, I was't having much luck. Trying to search across the space where the numbers could just increase and increase and never 'toggle' like they did in part 1 didn't work very well. I added a heuristic to conver the BFS into an A* search, thinking maybe if we direct the search space with a heuristic, it will all converge faster

let remaining: Vec<usize> = jolt.iter().zip(&joltage_goal).map(|(cur, goal)| goal - cur).collect();

let heuristic = remaining.iter().enumerate().map(|(i, &r)| {

let affect = buttons.iter().filter(|b| b[i] == 1).count();

if affect == 0 { usize::MAX } else { (r + affect - 1) / affect }

}).max().unwrap_or(0);

let priority = dist + 1 + heuristic;

heap.push(Reverse((priority, dist + 1, next_jolt)));

It did not. So, at nearly 3am, I gave up and went to bed. The plan? Try some dynamic programming in the morning when I was more awake.

Unlike the previous day, I didn't spring back up to attempt to program any ideas. Rather, I stared into the abyss until the darkness claimed my eyesight and consciousness. Not that I wasn't thinkinng about the problem at all, but I resisted the urge to flip on my overtired brain. Some DP in the morning should make it all go well, I thought.

10 minutes until I had to start work, and the dynamic programming was not going well. Attempting to press every button, even if I kept track of ways to bust out early, the act of BFS itself, or DFS, or any sort of memoization thereof, just didn't work. This was clearly not going to be the answer. I went to work, thought about it for a while, and came back after dinner and wrote down a comment:

fn fewest_presses_with_joltage(_buttons: Vec<Vec<u8>>, _jolt_goal: Vec<usize>) -> usize {

/* The input comes in like this:

* [ [1, 0], [0,1] ] [1, 1]

* and then the goal is to know we should press the buttons once each to make

* the initial state of [0,0] become [1, 1]. So, this is sorta like this:

*

* 1a 0b = 1 jolt

* 0a 1b = 1 jolt

*

* Which is REALLY similar to matrices in linear algebra.

*/

usize::MAX

}

That's right. Just like the day before, this wasn't a programming exercise. It was a math problem. I tossed on some good music, right-clicked, and pressed "loop" then proceeded to contemplate this train of thought in the comments, not really typing out any code itself yet, just dealing with the problem's input and how we'd need to fix things up:

* since you can never DECREASE the joltage, it only EVER goes up, then this is likke * * 1a + 0b = 1 * 0a + 1b = 1 * * And for a more complicated example, * [ [1, 0 ], [1, 1] ] [ 3, 2] * * a = 3 * a + b = 2 * * which of course trivially rduces down to press b1 once, b2 twice but... what about the case * of: * [ [1, 0 ], [1, 1], [ 0, 1]] [ 3, 2] * * this has MORE than 1 way to get to 3,2 and if we want to hit on the min b2 + b1, and not land * on b1 + b1 + b2 + b3 or some other combination, then we need to figure out how to get the smallest * one of these. * * We can never do a negative button press, so if we were to solve an question then we can toss out * any unbounded variable that needs to get loved by someone who takes a more negative viewpoint of the world. * * But first... convert the button input into a matrix since matrices are a good way to deal with * computing equations Linear algebra baby! one row per joltage output!

At this point, it was mostly a matter of writing the solver. But not without pain. I got the matrix code setup and mostly working before I streamed, and then post stream continued working on it. The usual suspects of stackoverflow, random write up posts from .edu domains, and I had a seemingly working version of Gaussian elimination. But it was… gross.

Rust doesn't have a for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) construction for looping. So,

when it came to a for loop in psuedo code that had a condition that stopped a loop based on two

potential cases, I ended up writing some gross looking code:

...

let mut col = 0;

loop {

if col >= variable_count && pivot_row >= rows {

break;

}

...

Though, this wasn't nearly as gross as dealing with a different beast. While testing, I was getting incorrect answers, and ended up grabbing some Javascript solver code to test things out, then swapped back to rust, and ran into what seemed like floating point errors. There's a write up here about just how bad these can be during Gaussian elimination, but I spent the next hour tweaking and fixing things until finally, I was just off by one.

The Javascript code was useful, and I tested it out and confirmed, by getting a star, that it was indeed working properly. And if I could get the rust code to behave the same, then I could call this day complete. The problem was now less about the actual puzzle, and more about getting the code ported to rust.

Unfortunately, the next day rolled around before I found my off by one error. But, I was done with that problem within 48 minutes and returned to staring at the disgusting matrix copypasta in front of me. I kept checking and rechecking the gross looking checks:

if pivot.abs() > 1e-4 && (pivot - 1.0).abs() > 1e-4 {

to no avail. I narrowed down the machine giving me the off by one error and isolated it into a unit test. I had the javascript code that worked after all, so I could run through and print out the result of each machine, then do the same on the rust side and diff the result to figure out which machine was causing the problem to inspect it closer:

#[test]

fn test_episilon_problem_machine_4_with_joltage() {

let (_, buttons, joltage_goal) = parse("[##....#...] (2,3,4,5,6,7) (0,1,2,3,4,6,9) (0,1,3,4,6,8,9) (1,2,3,4,6) (1,4,5,6,8,9) (2,4,5,8,9) (0,1,3,4,5,8,9) (0,1,2,6) (2,7,8,9) (1,2,4,8) (3,4,6,7,8,9) (0,2,5,7,8) (0,1,2,4,5,6,8,9) {79,95,119,80,137,88,128,63,122,126}");

assert_eq!(164, fewest_presses_with_joltage(buttons, joltage_goal));

}

Around this point icub3d's video on the day came out and I had figured out the puzzle to the speed of the program, just not the code. So I watched his breakdown, and looked at his really nice rust code that solved the problem in a WAY more readable way than the crap I had copied from stackoverflow and bent into the shape I needed.

I pulled down his code and adapted mine to use his Matrix class. Figuring that it must be the

elimination part that was wrong. It wasn't. I then tried out his back-substitution code. It also didn't

change my answer. Then, it wasn't floating point problems, and it wasn't bad math problems. It was the other

part of the code that was wrong. Can YOU spot the problem?

fn solve_for_free_variables(

free_vars: Vec<usize>,

normalized: &Vec<Vec<f64>>,

pivol_column: &Vec<usize>,

pivot_row: usize,

variable_count: usize,

) -> Vec<usize> {

let joltage_column = normalized[0].len() - 1;

// max free variable = max RHS, capped at something small-ish

let max_target: f64 = normalized.iter().fold(0.0, |acc, row| acc.max(row[joltage_column]));

let max_free_variable_value = max_target.floor().min(500.0); // 100 was too little, 500 seems ok.

let mut current_solution = vec![0usize; variable_count];

let mut min_sum_found = usize::MAX;

let mut min_solution = None;

enumerate_free_vars(

0,

&free_vars,

normalized,

pivol_column,

pivot_row,

variable_count,

joltage_column,

max_free_variable_value as usize,

&mut current_solution,

0,

&mut min_sum_found,

&mut min_solution,

);

min_solution.unwrap_or_else(|| vec![0; variable_count])

}

That's right! It's in THAT line! Mhm That's right. Yup. That one. Printing out the matrix at this point, you can see a bunch of lovely values in addition to the pivot and its friends:

[

[1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.5833333333333333 , 0.75 , 0.16666666666666669 , 40.333333333333336],

[0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.08333333333333331 , -0.75 , 0.16666666666666669 , 12.333333333333334],

[0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0833333333333335 , 0.2500000000000001, 0.16666666666666657 , 43.333333333333336],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, -0.24999999999999994, -0.75 , -0.5 , -15.0 ],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.16666666666666663 , -0.5 , 0.33333333333333337 , 22.666666666666664],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, -0.24999999999999994, 0.25 , 0.5 , 26.0 ],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, -0.5 , 0.5 , 0.0 , -1.0 ],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, -0.6666666666666666 , 1.0 , 0.6666666666666667 , 24.333333333333332],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.4166666666666667 , 0.25 , -0.16666666666666669, 22.666666666666668],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.08333333333333331 , 0.25 , 0.16666666666666669 , 8.333333333333334 ]

]

When I printed out the solution from the javascript, some of the variables were big. Bigger than what these two lines were producing for the bounds of this search:

let max_target: f64 = normalized.iter().fold(0.0, |acc, row| acc.max(row[joltage_column])); let max_free_variable_value = max_target.floor().min(501.0);

The joltage column is the last one, and so my code was limiting the search space to a max of 43 presses. You can probably imagine that just because the max presses for an individual joltage is X, that you still might need more than X presses to set all the other presses, especially if there's buttons on the machine that only impact one or two joltage numbers at a time.

With that figured out, I changed the max value to a flat 500 rather than based on the target values and out popped the correct answer. I think I probably could set it to be the sum of all the possible presses and that would work as well. But, I had been at this problem for 3 days at this point. So. Done and dusted. I'm not going to clean up the code, and I'm going to do what icub3d did next time, make a matrix class and handle things in there rather than dealing with someone's leftover italian cooking from stackoverflow.

Day 11 - EZClap ↩

As noted above, day 11 came, got defeated in less than an hour, and then I moved back over to day 10. I think the difficulty of this problem was probably intentional by the creator of advent of code; it's good to get a break from a tough problem to re-establish a bit of confidence in solving a problem quickly. Especially when you read it, think to yourself: Oh, I just need to DFS. And then find that, yes, indeed, you do only need to do DFS and you WON'T be searching your memory for math lessons of past decades.

This one was a networking problems of sorts. Basically, given an adjacency list and a start

point, define how many paths through the network manage to reach the "out" point. Parsing

the data was simple enough, it was just node: connection connection..., so it

wasn't nearly as involved as the previous days three part parse:

type ResultType = i64;

fn p1(raw_data: &str) -> ResultType {

let mut graph: HashMap<&str, Vec<&str>> = HashMap::new();

for line in raw_data.lines().filter(|l| !l.is_empty()) {

let (left, rest) = line.split_once(':').unwrap();

let rights: Vec<&str> = rest.split_whitespace().collect();

graph.insert(left, rights);

}

...

}

Then, it was just a matter of doing a depth first search to follow each branch from the initial

"you" node outward with a Vec masquerading as a stack:

let mut stack: Vec<Vec<&str>> = Vec::new();

stack.push(vec!["you"]);

let mut count: ResultType = 0;

while let Some(path) = stack.pop() {

let last = path[path.len() - 1];

// If we reached "out", count this path

if last == "out" {

count += 1;

continue;

}

// Otherwise explore neighbors

if let Some(next_nodes) = graph.get(last) {

for &next in next_nodes {

if !path.contains(&next) {

let mut new_path = path.clone();

new_path.push(next);

stack.push(new_path);

}

}

}

}

Yup. That's it. Compared to the previous day it was a massive relief. Reading the second part, I fully expected another painful punch to the face, but was pretty happy to see the problem change slightly but still remain, essentially, the same.

I gave it a naive implementation attempt first. The goal was to still count how many paths went from start to end, but we shifted the start point to a "svr" node and also needed to make sure that each path to the goal included two specific nodes: "dac" and "fft". Since DFS searches aaaalllll the way down, I just tossed in a conditional first to see how things would go:

// If we reached "out", count this path

if last == "out" {

if path.contains(&"dac") && path.contains(&"fft") {

count += 1;

}

continue;

}

Ran the program and it, as expected of a part 2, didn't stop anytime soon. Cool, I nodded my head and decided to toss a memoization hashmap at it:

...

let mut memo: HashMap<(&str, bool, bool), ResultType> = HashMap::new();

fn dfs<'a>(

node: &'a str,

dac_seen: bool,

fft_seen: bool,

graph: &HashMap<&'a str, Vec<&'a str>>,

memo: &mut HashMap<(&'a str, bool, bool), ResultType>,

) -> ResultType {

// did we pass the funny transform nodes yet?

let dac_seen = dac_seen || node == "dac";

let fft_seen = fft_seen || node == "fft";

// Is this a valid branch?

if node == "out" {

return if dac_seen && fft_seen { 1 } else { 0 };

}

// Did you get the memo?

if let Some(&cached) = memo.get(&(node, dac_seen, fft_seen)) {

return cached;

}

// Nope. Go forth, get the memo.

let mut total = 0;

if let Some(neighbors) = graph.get(node) {

for &next in neighbors {

total += dfs(next, dac_seen, fft_seen, graph, memo);

}

}

memo.insert((node, dac_seen, fft_seen), total);

total

}

dfs("svr", false, false, &graph, &mut memo)

Besides having to specify the lifetimes and some borrow checking fixing upper-ing, I had a working part 2 about 48 minutes after the day had started. So nice. What a nice feeling it was to get an easy problem after the other two painful ones. I then went back to working on day 10 as I chronicled above. Then, a little while later, it was time for the last day.

Day 12 - You're an amazon employee now. ↩

As I write this blog post, I actually haven't even started day 12 yet. I've thought about it. But I wanted to dump all my brain out about the other days first before starting in on this.

That said, I read the first part of the problem, sighed that it wasn't going to be an easy last day, and decided to refresh myself on how to solve knapsack problems. Why? Because this problem is a doozy. Here, let me give you the break down of why the moment I read it my heart sunk.

The elves are trying to figure out if there's enough space underneath all the Christmas trees for all the presents that need to go under them. Luckily for you and me, there's only 6 kinds of boxes they can put them in. Drawn in ascii, these can look like this:

0: 1: 2: 3: 4: 5: ##. ### #.# ### ### ### .## .## ### #.. ### ##. ..# ##. #.# ### ..# #..

The boxes are always 3x3 in size, and the regions under the trees are represented like this

40x42: 38 37 45 42 54 41

Where the first part before the : is the dimensions of the overall area, and then

the list of numbers matches up to the indices of the shapes and represents how many of said

shape you need to fit into that region. If you don't have a computer science background, you

may think: pffft, what's so hard about that? It's just playing tetris!

So, this is the knapsack problem. Or rather, it's a variation on it. And a harder variation on it to boot. This belongs in the problems in computer science that exist in the fancy world of "NP". AKA: They are hard as balls, have no optimal solution in any general sense, and are the subject of research papers done by the biggest brained of academia.

So. Big shot. Still pfft-ing and saying tetris is easy? Hm? HM?

So, since I wasn't done with day 10 part 2 yet, I set this day's trouble aside with a plan to read the wikipedia page on the Knapsack problem later. Parsing the input would be interesting, but until I read through some articles I figured I wouldn't really know what to parse the input into since for all I knew, it'd be another: ignore the input and just turn it into a set of linear equations again. 4

So, resolving myself to fate. I decided to sleep and get well rested before tackling the problem on the weekend. Luckily for me, the workplace leaderboard showed no signs of anyone else trying to tackle the NP-Complete problem yet, so I at least wasn't about to lose to someone with a red stapler in the basement. The next morning I woke up around 6am, before my morning fitness boxing 3 and read through the wikipedia page on bin packing on my phone. Then I sighed, rolled over in bed, and buried my face into the pillow.

I did have some interesting thoughts while lamenting my fate:

- If I could fit together pieces into perfect rectangles, that would make it maybe easier, and I could reduce the search space? Or at least make it tractable in some way?

- I hadn't checked the actual input yet, maybe the regions would be small enough to fit into bits? As in, just in 16x16 grids, and so the whole grid could be represented as bitmasks and then the computer could do a bunch of super fast swish swoosh swaaashhh against it and kapoof: solution!

- Maybe someone had made a breakthrough in recent years and there was some sort of new algorithm that I just hadn't heard of that I needed to implement?

I went off to my usual Saturday morning haunt, read some comedy manga and nearly spit beef stew out of my nose trying to suppress my laughter while I was in public to this:

Then, it was time to lock in. I continued reading some more wikipedia:

Each link I clicked and read through continued the dread. There was no way in hell I was going to be able to figure this out, huh? But… it couldn't be impossible right? I mean, Advent of Code problems are always solveable in some way, and even if this year was only 12 days, that wouldn't mean that he'd give us one that would literally take us 12 days to run. Right?

So, I decided to parse the input while I kept chewing on the articles I was reading.

It was actually pretty fun, since I wasn't pressed for time by Midnight/Work, I decided

to take my time with it and implement a pattern I had seen in icub3d's videos. Using the

From trait to handle parsing the chunks:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]

struct Shape {

index: u8,

shape: [[usize; 3]; 3],

}

impl From<&str> for Shape {

// Input is of the form, index:\n...\n###\n.... where # and . indicate shape or not

fn from(string: &str) -> Shape {

// Blog note: don't forget to use ! in front of line.is_empty

let mut lines = string

.lines()

.take_while(|line| !line.is_empty())

.enumerate();

let idx = lines.next().unwrap().1.split_once(":").unwrap().0;

let mut s = Shape {

index: idx.parse().unwrap(),

shape: [[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0]],

};

for (row, line) in lines {

for c in 0..3 {

s.shape[row - 1][c] = if let Some(ch) = line.chars().nth(c) {

if ch == '#' { 1 } else { 0 }

} else {

0

}

}

}

s

}

}

Now, I'm pretty sure this is going against the recommendations made in the From trait documentation.

Note: This trait must not fail. The From trait is intended for perfect conversions. If the conversion can fail or is not perfect, use TryFrom.

But. I'm lazy. I might be "taking my time", but that doesn't mean I'm going to not use unwrap

on a puzzle problem that's not part of a great system that would need to care about errors. If I screw up

the parsing, I'll catch it right away. After all. I added tests:

#[test]

fn test_parse() {

let full: Shape = "0:\n###\n###\n###".into();

assert_eq!(full.shape, [[1, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1]]);

assert_eq!(full.index, 0);

let partial: Shape = "1:\n.##\n#.#\n##.".into();

assert_eq!(partial.shape, [[0, 1, 1], [1, 0, 1], [1, 1, 0]]);

assert_eq!(partial.index, 1);

let none: Shape = "2:\n...\n...\n...".into();

assert_eq!(none.shape, [[0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0]]);

assert_eq!(none.index, 2);

}

While I had been agonizing over what the input should shape up to be, I figure'd that if I did stumble across an efficient algorithm, I could go ahead and write a conversion function as needed. For the time being, putting the grid into a list of 1s and 0s felt like a step in the right direction to me.

Once I had the shape parsed, I setup the region struct and parsing as well:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Region {

width: u8,

height: u8,

quantity_to_fit_per_shape: [usize; NUM_MACHINES],

}

impl From<&str> for Region {

fn from(string: &str) -> Region {

let (sizing, numbers) = string.split_once(":").unwrap();

let (width, height) = sizing.split_once("x").unwrap();

let mut counts = [0usize; NUM_MACHINES];

let numbers = numbers

.split_whitespace()

.map(|n| n.parse().unwrap())

.take(NUM_MACHINES)

.enumerate();

for (i, n) in numbers {

counts[i] = n;

}

Region {

width: width.parse().unwrap(),

height: height.parse().unwrap(),

quantity_to_fit_per_shape: counts,

}

}

}

I opted to use a constant for the fact that the example, and the input had only 6 types of present shapes defined. While I was setting this up and testing the parse against the input, I noticed something. All the real input values were pretty big!

I sorted the input list to check and confirmed: all the regions were in the upper 40x40s, but also none of the regions were ever greater than 50x50. That's too big for my bitmask idea, but it did spark a couple neurons together:

40x42: 38 37 45 42 54 41

If there were too many buttons to even fit into the region, then I could probably toss out the idea to ever consider that problem. Like, if you've got a grid of 2x2, you can't ever fit a 3x3 square in it. Similar, if you've got a 4x4 grid, you can't fit 5 2x2 squares into it! I didn't do anything with this idea yet, but filed it away for when I was going to write non-parsing code. Which, was basically now, so I started setting up my skeleton:

type ResultType = i64;

fn p1(raw_data: &str) -> ResultType {

let shapes: Vec<Shape> = raw_data

.split("\n\n")

.take(NUM_MACHINES)

.map(Shape::from)

.collect();

let regions: Vec<Region> = raw_data

.lines()

.skip_while(|line| !line.contains("x"))

.map(Region::from)

.collect();

let mut regions_able_to_fit_all_presents = 0;

for region in regions {

if region.can_fit(&shapes[..]) {

regions_able_to_fit_all_presents += 1;

}

}

regions_able_to_fit_all_presents

}

Then I defined my can_fit function:

impl Region {

fn can_fit(&self, regions: &[Shape]) -> bool {

self.can_fit_n(regions) != 0

}

fn can_fit_n(&self, regions: &[Shape]) -> usize {

// can_fit_n so that we can more easily test the example cases

0

}

}

I figured that since the example input show cased how many shapes they could it into the regions, that I'd have both a boolean can fit/can't fit function AND a function that returned how many blocks I thought I was able to fit. That way we could write unit tests against it. Hey, that's a good way to procrastinate some more:

fn example_regions() -> [Region; 3] {

[

...

Region {

width: 12,

height: 5,

quantity_to_fit_per_shape: [1, 0, 1, 0, 3, 2],

},

]

}

fn example_shapes() -> [Shape; 6] {

[

...

Shape {

index: 5,

shape: [[1, 1, 1], [0, 1, 0], [1, 1, 1]],

},

]

}

...

#[test]

fn test_region_3_example() {

let region = &example_regions()[2];

let shapes = example_shapes();

assert_eq!(region.can_fit_n(&shapes[..]), 0);

}

Great. A passing unit test! It passes for all the wrong reasons, but it would be a starting point. I guess. Getting the momentum going was the best thing I could think of. If I was going to run into a wall, I wanted to hit it full force just in case I'd have a breakthrough. I wrote up a rotation method next. We'd need that to DFS the search space. There were a lot of potential configurations after all.

impl Shape {

fn rotated(&self) -> Shape {

let mut rotated_shape = [[0usize; 3]; 3];

// rotate 90 degree clockwise

// [1,2,3]

// [4,5,6]

// [7,8,9]

// ------>|

// v

// [7,4,1]

// [8,5,2]

// [9,6,3]

// row 0 becomes col 2

// row 1 becomes col 1

// row 2 becomes col 0

rotated_shape[0][2] = self.shape[0][0];

rotated_shape[1][2] = self.shape[0][1];

rotated_shape[2][2] = self.shape[0][2];

rotated_shape[0][1] = self.shape[1][0];

rotated_shape[1][1] = self.shape[1][1];

rotated_shape[2][1] = self.shape[1][2];

rotated_shape[0][0] = self.shape[2][0];

rotated_shape[1][0] = self.shape[2][1];

rotated_shape[2][0] = self.shape[2][2];

Shape {

index: self.index,

shape: rotated_shape,

}

}

}

And, it'd be easier to define the search space if I had a way to take the requested count of each present from a region and turn it into a list of those presents. Then I could do something like drain the queue or something as I recursed and result in that being my base case. Maybe. I mean, this being NP-Complete means that it might not actually work at all to try to use dynamic programming on this.

fn shapes_for_region(&self, shape_definitions: &[Shape]) -> Vec<Shape> {

let mut shapes = Vec::new();

for i in 0..self.quantity_to_fit_per_shape.len() {

let count = self.quantity_to_fit_per_shape[i];

for _ in 0..count {

let shape = shape_definitions[i].clone();

shapes.push(shape);

}

}

shapes

}

Lovely, I can get a list of shapes, I can rotate them all. Now I just need a grid I suppose. But that feeling hit me again about not knowing if I was representing things properly or not. I was also just feeling like it was intractable again. I sort of wanted to just throw in the towel, I mean, there was no way I was going to be able to solve… 1000 puzzles in any reasonable amount of time. Right?

So, I opened up the video I had seen in my feed earlier that day. I paused it before it started playing, sighing. But I did notice that iCub3d had linked a research paper. Aha! Ok! Hope restored, I don't need to watch the spoiler video yet, we can go ahead and read a bit of this paper and find out what we might be missing!

But what stood out to me was that the "enveloping polygon" method felt like a good idea. And a lot like my idea from earlier about the amount requested being too high to ever fit. Seeing the polygons visually got me thinking though. What if my answer was actually that none of the inputs are even solvable? That'd be sort of funny. I continued reading through the paper, saw a mention of "mixed-integer linear programming", and my heart sank. Oh no. It's another math problem isn't it?

So I went back to the video, sighed, and hit play. I guess I'll just be learning something new today. About 20 seconds in he mentioned "it was kind of a trolly" day. So I paused it. Wait. Are we talking about the same day? Are we talking about the NP-Complete problem being trolly? Or? Hm. What if just, none of them are solveable? How many inputs are there? 1000?

Nope. Checked and the website let me know that the problem's answer was lower and my 1000 was too high. So it's not that. Is it something like, the shapes arranged on the board spell something that points you to the answer? I went ahead and let the video play while I kept thinking about when that potential troll could be. I mean, I remember last year, the last day was easy. Maybe I missed something in the problem description?

4:33 into the video, icub3d was just reading the problem and said something along the lines of:

you have to ask yourself, is that possible?

Made me think: wait what about my idea from before? Maybe a bunch of the problems were just too big to solve anyway, or maybe this was something like 999 of the puzzles are invalid and the last one we have to check by hand? Maybe something like this. Hopeful, I paused the video again lest it give us spoilers, and then threw together a quick check

impl Shape {

...

fn area(&self) -> usize {

let mut a = 0;

for r in 0..3 {

for c in 0..3 {

a += self.shape[r][c];

}

}

a

}

}

It's a good thing I did 0 and 1 for the shape! Computing the number of tiles used is really simple. With that made, it was easy to update my can fit function to test it out a bit.

impl Shape {

fn can_fit_n(&self, shapes: &[Shape]) -> usize {

// can_fit_n so that we can more easily test the example cases

let shapes_to_fit = self.shapes_for_region(shapes);

let total_shape_area = shapes_to_fit.iter().fold(0, |a, s| a + s.area());

if total_shape_area > self.width as usize * self.height as usize {

return 0;

}

}

}

I added a println out of curiousity and saw a stream of

1368 does not fit in 35x39 1825 does not fit in 48x38 1902 does not fit in 50x38 2351 does not fit in 50x47 2103 does not fit in 50x42 2109 does not fit in 49x43 2207 does not fit in 49x45 ...

Oh hey, it's catching things! 409 puzzles to be precise! That's cool. As a bit of a hail mary, I figured that at least it would be nice to confirm that this number was too high. So, that's 1000 inputs, 409 items to remove, and then if that's too low then there's something potentially wrong with my area function. And,

Oh!

That's advent of code 2025 complete! NP-Complete! Done!!! Four hours of reading wikipedia, articles, and agonizing over potentially having to write a DP search, complete!

We're SAVED! We don't have to become amazon factory floor workers loading trucks upon trucks up with boxes and solving this tetris problem every day and night! We can go back, with a light and happy heart, to our 20 games challenge postings!

Closing thoughts ↩

Man. The last few days were a rollercoaster of emotion. Just like last year I managed to finish the various problems. But also like last year, the math problem ones really screwed me over. I've got a book that goes over a bunch of math that relates to game development that I should probably read. Heck, half the time I feel like I should just go over high school math again.

But, I think the main thing is that I had fun. This year had less pressure for me. The fact that it was only twelve days was nice. It means I don't have to scramble every day to balance sleep and code. I loved the energy of "every one is doing Advent!" that the IRC channels had last year, and this year was a bit more tame, but there were still folks to chat with. And I enjoyed myself.

Though. I am tired. The last 3 days of the challenge were, well, challenging. And between a really really busy work month, AND staying up late to try to stick with and keep up with the advent calendar's new challenge each day, I need a nap. Heck, I'm fighting my eyes as I write this post. But, I wanted to finish it up. So. Apologies for any typos, and I hope that this post was somewhat interesting, or maybe helpful if you were getting stuck at all on some of the problems.

See you all next year! Merry Christmas!