Day 1 - I'm rusty at rust ↩

The first day was, as usual, pretty simple and straightforward. Just like last year, the first problem involved a list to parse and do some operations with. Unlike last year I wasn't in the middle of learning rust and so I parsed the input just fine once I refreshed my memory a bit by looking at how I did it last year.

It was impressive to me just how much I forgot in the span of a few months. Use it or lose it definitely applies for languages you pick up in your spare time. That, and the borrow checker and the way Strings are extremely annoying in rust made for more fighting with the compiler than I'd like to admit. But, 37 minutes after midnight I had my part 1 done and dusted.

The actual problem was to take something like L20 and R192 and

rotate a radial lock left or right the specified number of clicks. The solution to the

problem being how many times you landed exactly on 0. Which,

of course, I misread at first for how many times you go past zero. Besides

my lack of comprehension 1, the

only tricky thing is that the first idea that comes to mind isn't really correct.

Whenever you start explaining to a programmer that a number wraps around, they'll jump to

thinking about the modulo operator. That's

all well and good for the rightward turns that advance the dial's value upwards. However,

moving leftward from say, 1 to 99 (the dial only has 100 numbers on it) would have you doing

something like (current_value - turn_by) % 100. Which uh. Isn't really well defined.

Now, Rust has a euclidian remainder method built in you can use. However! I am not well versed enough in the standard library, nor am I smart enough to even think that something such as "euclidian" modulo might exist in the first place! No, I'm far too out of the loop for that, and so, I opted to KISS it2

// start is just the current position of the dial as we process

// each operation. This is just a snippet and not the full solution.

match op.chars().take(1).last().unwrap() {

'R' => {

let num:i32 = op[1..].parse().unwrap();

for i in 0..num {

start+=1;

if start == 100 {

start = 0

}

}

}

'L' => {

let num: i32 = op[1..].parse().unwrap();

for i in 0..num {

start-=1;

if start == -1 {

start = 99

}

}

},

_ => todo!()

}

No fancy math or thinking about how rust might implement negative numbers for its %

operations. Just tell the computer to wrap. The nice thing about that, is that, since I wasn't

doing any "bulk" operations by adding all at once, the logic and level of overhead in my head

late at night was minimized. I might be tired, but even I can understand what one plus one is

past midnight so I can focus on the real problems. Like the borrow checker telling me I moved

an iterator inside of its own for loop or whatever other nonsense I ran into while forgeting

to write unwrap for the 3rd time on an option.

I got a kick out of reading part 2 of the problem, since it was what I had misconstrued the problem as at first! Now, we had to count how many times we passed 0 while turning the dial. Besides a silly off by one error, I was done 15 minutes later and went to bed. An easy first day, and a harsh reminder that easy string manipulations are not where rust shines, at all.

Day 2 - I overthunked it a bit ↩

Day two was another day of fighting the language I've forgotten more than figuring out any particular challenge with the puzzle itself. Or at least that's what it felt like. Refreshing my memory by staring at the git log and seeing that part 1 took me around 55 minutes, in actuality: It was moreso the late night brain preventing me from realizing a simple optimization that caused the delay. Once the last minute brain blast kicked in, part 2 was done in less than 10 minutes after that.

What was day 2's challenge you ask? Given a list of ranges, count how many numbers between

them (inclusive) were the same number repeated twice. So, 11 is a valid thing

to count since it's one and one. 1212 is countable since it's 12 and 12,

but something like 12312 is no good because the 3 in the middle there means

the 12s aren't repeated twice.

That's my wording of the problem, this is not how it was worded on the AoC website. Due to that, and a small degree of overthinking, I implemented a window against the input and brute-force checked if there was a singular repeated set of numbers in the input:

// (A) if id.len() % 2 == 1 { return false } let window_size = id.len()/2; (B) let chars: Vec<char> = id.to_string().chars().collect(); let mut chunk_iter = chars.chunks(window_size); let mut seen = 0; let left = chunk_iter.next(); let right = chunk_iter.next(); if right.is_none() { return false; } (C) if left.unwrap()[0] == '0' || right.unwrap()[0] == '0' || left.unwrap().len() != right.unwrap().len() { return false } if left.unwrap() == right.unwrap() { seen += 1 } // we saw 1010, but not 101010 (B) if seen == 1 { return true } false

To make my explanation easier, I've marked three points of interest in the snippet above:

- I forgot this at first, resulting in 111 being considered. But since the repeat must happen exactly twice, all id's will always have a length divisible by 2, and so we can prevent that issue entirely by just bailing out early with this check.

-

I was overthinking at first, it being late in the evening/early in the morning, I didn't

stop myself from that. So, I actually ended up implementing code that I'd need for part 2

first by having a window size, once I reread the problem enough to realize I only needed

2 chunks, I ditched the loop expanding that size and replaced it with the simple length

based split. Though, this didn't prevent me from having a check for

seenonly once, despite not actually needing that anymore. Hm. Funny what you realize when you write a blog post and review your work from a few days ago more thoroughly. -

The word problem explicitly noted that a digit wasn't a real number if it began with a 0,

so you would never consider something like

100210to have a 2 as its second value if you were chunking the data up with a window size of 2.100210. I put in these checks, but honestly, I don't know if they're actually neccesary for part 1 or not. Either way, the length check on the two halves was added before I did the early return in (A), so that's also dead code I think. Ahem. Funny what you realize when you write a blog post and review your work from a few days ago more thoroughly.

All in all though, it wasn't too bad. And my overthinking on part 1 ended up letting my deal with the change in part 2 in short order. As you may have surmised already, part 2 changed the rules from repeating exactly twice, to repeating at least twice. So, I added my expanding window size back into my id checker function and also more explicitly checked "left" and "right" to keep things simpler:

for window_size in 1..id.len() {

let chars: Vec<char> = id.to_string().chars().collect();

let mut chunk_iter = chars.chunks(window_size);

let mut seen = 0;

let pattern = chunk_iter.next();

let mut right = chunk_iter.next();

while right.is_some() {

if pattern.unwrap().len() != right.unwrap().len() {

right = None;

seen = 0;

continue;

}

if pattern.unwrap() != right.unwrap() {

seen = 0;

right = None;

continue;

} else {

seen += 1

}

right = chunk_iter.next();

}

if seen > 0 {

return true

}

}

false

I do like that rust has a chunks function.

as it makes this sort of thing much easier. While I still reserve the right to complain about string manipulation

in rust, I will also give credit where credit is due. I didn't have to make a loop that moved around i

and j cursor-type indices around to track subsets of the string.

A nice little optimization I had in place was that right = None you see there. Since the entire

ID needed to be a repeating number according to the rules, if you had something like 1010221010

then you could stop processing and reject the value once you hit on 22 with a window size of 2.

I don't think the search spaces is really that big, but still, it makes me happy when I realize a way to avoid

having the computer do extra work.

Doing extra work is something I wish I had less of. As the next day, well…

Day 3 - I was late ↩

Last year I was up and ready every single day at midnight. Plowing away. Sometimes staying up til 4am in some cases to get the puzzle done before going to bed. Yes, Yes, I know, not a great thing to do on a work day. But hey, I can't help getting nerd sniped.

Or at least, last year I couldn't. This time around, I'm just getting over an absolutely massive crunch at work that has left me as tired as a nurse's arm at a cryobank on December 1st3. As such, I ended up falling asleep early the night before day 3's problem was released and started it a half hour before my workday began. Luckily, day 3 part one was pretty simple! In 14 minutes I had a very simple brute force method to compute the total "joltage":

fn compute_joltage_p1(line: &str) -> usize {

let mut joltage = 0;

let bank_length = line.len();

for (left_idx, left) in line.chars().enumerate() {

if left == '0' {

continue;

}

// Skip it if you can't turn on N batteries anyway

if left_idx > bank_length - 2 {

continue;

}

let mut banks_on = String::new();

banks_on.push(left);

for right in line.chars().skip(left_idx + 1) {

let combined: usize = format!("{}{}", left, right).parse().expect("Cant convert left and right to number");

if combined > joltage {

joltage = combined;

}

}

}

joltage

}

Joltage being the largest number you can create from a single battery bank by turning on

only two of its digits without rearranging them. So, if you had a battery bank like 1234,

then you could create 34 jolts by turning on digits 3 and 4. Pretty straightforward,

and since we can't re-arrange things, we just always move rightward and find the biggest pair of

digits.

My brute force O(N2) solution here wasn't what I actually wanted to implement by the way. Yet another place where using a language I've forgotten most of is a detriment to my productivity. What I wanted to do was have two cursors, slide them forward for as long as I had space to, and that way, be able to compute the joltage in a single pass.

But. I had 30 minutes before work, was feeling bad that I had fallen asleep by accident before midnight, and was just trying to get at least part 1 done before clocking in, and thus. Rather than fighting with my memory on how to properly write rust code, I just did what I knew would work without much fuss.

I read part 2's description, thought about brute forcing it, and then just jotted down my half baked thoughts before heading into work. Said half baked thoughts were:

-fn compute_joltage(line: &str) -> usize { +fn compute_joltage(line: &str, allowed_batteries_on: usize) -> usize { let mut joltage = 0; + let bank_length = line.len(); - for (leftIndex, left) in line.chars().enumerate() { + for (left_idx, left) in line.chars().enumerate() { if left == '0' { continue; } - for right in line.chars().skip(leftIndex + 1) { + // Skip it if you can't turn on N batteries anyway + if left_idx > bank_length - allowed_batteries_on { + continue; + } + let mut banks_on = String::new(); + banks_on.push(left); + for right in line.chars().skip(left_idx + 1) { + let mut bank = banks_on.clone(); + // turn on "allowed_batteries_on" banks then check joltage. + // we can only ever move rightwards since you can't re-arrange batteries + // so it's a question of [L,_,_,+,_,_+] which banks to the right of the L should we turn on for max jolt? + // TODO: get the permutation to the right. Perhaps as a bitset for added fun. + // 4095 is the binary number of 1111 1111 1111 so perhaps using all numebrs between there to flip on and + // check joltage would work. But for now. To work I go.

This idea didn't pan out when I returned to it with less I just woke up brain. Even if a bit set idea worked, twelve isn't enough. Sure, 12 places where the numbers could go is true enough, but the battery banks in the actual input were 100 large or so. So, when I implemented this idea (knowing full well it wouldn't pan out but wanting to see how far it could go anyway), I was unsurprised to see it just spike my CPU and output nothing while it thought. And thought. And thought. Still, I like the idea at least:

use itertools::Itertools;

fn compute_joltage(line: &str, allowed_batteries_on: usize) -> usize {

let mut joltage = 0;

let mut holes: Vec<bool> = Vec::new();

for (idx, _) in line.chars().enumerate() {

let state = if idx < allowed_batteries_on { true } else { false };

holes.push(state);

}

let len = holes.len();

let mut combinations = holes.into_iter().permutations(len).unique();

while let Some(combination) = combinations.next() {

let mut bank = String::from("");

for (idx, &state) in combination.iter().enumerate() {

if state {

bank.push_str(&line[idx..idx + 1]);

}

}

let combination_joltage: usize = bank.parse().expect("Cant convert combination to number");

if combination_joltage > joltage {

joltage = combination_joltage

}

}

return joltage;

}

If nothing else. It's fun to think about different solutions to a problem, even if they're intractable. Since I knew it wouldn't work, I used itertools (despite usually not using 3rd party libraries in AoC where possible) to generate the potential combinations of the boolean list where only 12 items are ever set to true. If I remember my math correctly, I believe this would be P(100, 12) since order matters and replacements aren't allowed since they're all the same value. The amount of potential holes to check in this case would be 503,153,364,153,791,070,720,000 4 which isn't a number of times you'd want to loop and do anything on your personal computer.

Not to mention that I think itertool wouldn't even bother creating it as whenever I'd run the program,

even with a println inside of the loop, I'd see it spit out a few items, then nothing. I assume internally

to the library it was calculing the .next() value and thinking about sextillions or something.

Either way, I ate my dinner after work, watched some anime, and then put this aside and worked on a different

idea before streaming that day.

We need a way to constrain the search space. And so, given what I did for part 1 and only having to think about the values to the right. I figured we could do something similar. I thought about it, tried to write some code, got stuck, threw out what I was doing, and repeated that cycle a few more times. Sensing that I was close to a good idea, I went over to the reddit mega thread for AoC to see if I could spot any sort of non-spoiler hint.

I'm not above using hints in these types of things. It's obviously more rewarding to come up with your own idea of how to solve the problem all by yourself. But between the choice of verbally berating myself whilst slamming my head on the deck, and figuring out the tricky bit of writing the algorithm down after someone describes something that might work, I'll take the former. As such, I stumbled onto a great hint that didn't give the entire algorithm away (unless you watched the whole thing, which I didn't), and clued me in to a data structure I hadn't been thinking about.

// stop being dumb and use a stack.

let mut selected_batteries = Vec::with_capacity(allowed_batteries_on);

let length = line.chars().count();

let mut remaining_batteries = line.chars().enumerate();

while let Some((idx, battery_value)) = remaining_batteries.next() {

let battery = battery_value as i32 - 0x30;

// Seed value for the stack.

if idx < 1 {

selected_batteries.push(battery);

continue;

}

// TODO If the top fo the stack is less than the current battery then

// we should be able to replace it since it will make a bigger number.

// we should be able to do this WHILE the top is less, unless we have

// only a few more batteries to go, in which case we'd be better off

// just appending it so the number can grow to its maximum size.

let top = selected_batteries.pop().expect("The top should never be empty");

let remaining_battery_count = length - idx;

let stack_size = selected_batteries.len();

// this is all wrong ugh. but I know what I want to do its just hard to express it

let left_to_check = length - idx;

if battery > top && stack_size < allowed_batteries_on {

while let Some((_, battery_value)) = remaining_batteries.next() {

let battery = battery_value as i32 - 0x30;

if battery <= top {

break;

}

selected_batteries.push(battery);

}

selected_batteries.push(battery);

continue;

}

if battery == top {

selected_batteries.push(top);

selected_batteries.push(battery);

continue

}

// In the case where battery is less than the top

if stack_size < allowed_batteries_on {

selected_batteries.push(top);

selected_batteries.push(battery);

}

}

As you can see by the comment in the middle. My pre-stream checkpoint wasn't quite working yet. But I figured clearing my head and playing some Ace Attorney would clear my head out and get me back on the right track to finish the day's problem up before the next one unlocked. This seemed to help, as I was able to not only solve the stack rightward funky problem, but also to re-discover a fun little trick!

let battery_value = battery_character as u8 - b'0';

Subtracting the binary value of the character for 0 results in an easy way to convert any digit 0 - 9 into their actual numeric value without having to call parse. Pretty fun to do and it removes one little unwrap in my code. The algorithm to figure out the max joltage for any sized battery became:

fn compute_joltage(battery_bank: &str, allowed_batteries_on: usize) -> usize {

let mut enabled_digits = Vec::with_capacity(allowed_batteries_on);

let digits = battery_bank.chars().enumerate();

let length = battery_bank.chars().count();

for (idx, battery_character) in digits {

let battery_value = battery_character as u8 - b'0';

while let Some(&top) = enabled_digits.last() {

let enabled_count = enabled_digits.len();

let remaining_digit_count = length - idx;

let battery_provides_better_joltage = top < battery_value;

let can_still_fill_bank_to_limit = enabled_count + remaining_digit_count > allowed_batteries_on;

if battery_provides_better_joltage && can_still_fill_bank_to_limit {

enabled_digits.pop();

} else {

break;

}

}

if enabled_digits.len() < allowed_batteries_on {

enabled_digits.push(battery_value);

}

}

let mut combined = String::with_capacity(allowed_batteries_on);

for battery in enabled_digits {

combined.push((battery + b'0') as char);

}

combined.parse().expect("joltage did not convert")

}

You can see I was trying to name my variables in a way my sleepy head could follow.

The calculation for can_still_fill_bank_to_limit in particular was the

one that kept giving me mental blockage. Like, you know when you're working on something,

you know you know how to do something, but each time you think about it you just

feel your attention drift over somewhere else? Like your brain refuses to stay focused

on the single point that actually matters to you? Yeah. That kept happening. I guess all

that attorney-ing really helped because I got the dang thing right after hearing the game's

cries against my brain's crimes:

Anyway. Happy with the result of finally getting what I knew in my head would work out onto the code. I nodded my head and smiled. A slightly tricky problem done! What next, Advent of Code? What shall I defeat next?! Bring it on! カカッテコイ (๑•̀ᗝ•́)૭ I can deal with whatever you've got next Advent Calendar! Come on!

Day 4 - An easy opponent ↩

All my fire and brimstone at the ready. I clicked open that puzzle ready to light the place up with my fingers of fury. Only to be greeted by what felt like an old familiar friend.

..@@.@@@@. @@@.@.@.@@ @@@@@.@.@@ @.@@@@..@. @@.@@@@.@@ .@@@@@@@.@ .@.@.@.@@@ @.@@@.@@@@ .@@@@@@@@. @.@.@@@.@.

Oh ho! A GRID! There were a lot of grids last year, and they were some of my favorite puzzles because they lent themselves to making amusing little animations. So I had some rust code ready to go pretty quickly to grab the data and put it into a useable form:

let matrix: Vec<Vec<char>> = input

.lines()

.filter(|line| !line.is_empty())

.map(|line| line.chars().collect())

.collect();

let rows = matrix.len();

let cols = matrix.get(0).map(|m| m.len()).unwrap_or(0);

With a grid ready to traverse, I read the rest of the problem and found that it was a pretty

simple question of counting how many neighbors certain types of tiles had available. Outside

the usual user errors of isize versus usize I had my solution complete

28 minutes after starting.

// just loop over the matrix and accumulate based on whether or not this meets the criteria.

fn count_paper_around_point(matrix: &Vec<Vec<char>>, row: isize, col: isize) -> usize {

let rows = matrix.len() as isize;

let cols = matrix.get(0).map(|m| m.len()).unwrap_or(0) as isize;

let mut positions_around_us = Vec::with_capacity(8);

for i in -1..=1 {

for j in -1..=1 {

if i == 0 && j == 0 {

continue;

}

if 0 <= row + i && row + i < rows {

if 0 <= col + j && col + j < cols {

let row = (row + i) as usize;

let col = (col + j) as usize;

positions_around_us.push(matrix[row][col] == '@');

}

}

}

}

positions_around_us.iter().filter(|&is_paper| *is_paper).count()

}

I expected part two to ramp up the difficulty. But was pleasantly surprised when it took literally 3 minutes to read through, tweak the program, and submit the answer. I'm not a speed-programmer or anything like that. But it does feel good when you wrap something up early and can go to bed on time. Especially when the day before was crushing me a bit up until my attorney assisted me. Unlike the previous day, brute force worked just fine:

let mut result = 0;

loop {

let mut total_removed = 0;

for y in 0..rows {

for x in 0..cols {

if matrix[y][x] == '@' {

if count_paper_around_point(&matrix, y as isize, x as isize) < 4 {

result += 1;

total_removed += 1;

matrix[y][x] = 'x';

}

}

}

}

if total_removed == 0 {

break;

}

}

The goal of the day, as you might be able to tell by the break condition, was to attempt to remove as much paper as possible from the space represented by the grid. Paper can only be removed if there's less than 4 stacks around a spot, and of course, once you remove that, it opens up the potential that you could revisit it and remove more.

I would bet that there's a very smart, clever, and non-wasteful way to do this. But honestly, doing full sweeps across the grid until nothing twitched anymore worked just fine. I could reduce the amount of checks perhaps by representing that data more sparesly with an adjacency list rather than the full matrix I guess, but eh, the above worked fine and solved quickly enough for me to go and rest. And remember how the other day I really needed that rest?

Day 5 - Oops, I forgot stay up again ↩

Just like before, I ended up going to bed early. I wasn't even thinking about advent of code at the end of day 4. Most likely because I had gone out to play trivia with some friends and we actually won! We used to win pretty often, but then these two other regular teams started bringing 12 people each time and just… ahem. I digress. The drama and legality of people with more friends having better chances at winning random trivial questions isn't really the culprit here.

Rather, it was the fact that I absolutely crushed the "math" round of the evening, had my usual three social vodkas, and came back home to play some pokemon for 40 minutes on stream before immediately falling asleep that stopped me coding at midnight. 5 So, when I woke up at 6am and realized I hadn't even looked at the problem yet, I cursed. There's another dude on the leaderboard at work who's really smart and I was ahead of him by two points. Not so much anymore after this.

Anyway, the problem wasn't a terribly difficult one. According to git I created my rust

project at 5:47am and then at 6:04am submitted my part one solution. The goal was to look

at a series of ranges, like 12-20 or 18-30 and check to see how

many numbers in a seperate list happened to be within them. Really simple straightforward

stuff. I just made a bunch of tuples and then looped:

fn p1(raw_data: &str) {

let rules: Vec<(usize, usize)> = raw_data.lines()

.take_while(|line| !line.is_empty())

.map(|line| {

let mut raw_range = line.split("-");

let low: usize = raw_range.next().expect("couldnt read low").parse().expect("couldnt convert low");

let high: usize = raw_range.next().expect("couldnt read high").parse().expect("couldnt convert high");

(low, high)

}).collect();

let skip_length = raw_data.lines().take_while(|line| !line.is_empty()).count() + 1 ;

let ids: Vec<usize> = raw_data.lines().skip(skip_length).map(|line| {

let id: usize = line.parse().expect("Id could not become a number");

id

}).collect();

let mut fresh_count = 0;

for id in ids {

let mut fresh = false;

for &(low, high) in &rules {

fresh = fresh || low <= id && id <= high;

}

if fresh {

fresh_count += 1;

}

}

println!("{:?}", fresh_count);

}

The inefficiency of my creating multiple iteraters across the raw input aside, this all worked and let me stare at the second part of the problem for an hour. Unfortunately for me, part 2 was harder for me to completely grok. I think probably because I hadn't actually woken up fully yet. I quite literally sprung up out of my bed to sit and type up the puzzle solution first thing. So, that initial boost of energy quelled itself just as shortly.

Part two wasn't actually that hard. I just wasn't thinking very clearly. I did make myself some nice helpers though. Rather than simple tuples of numbers this time, I attempted to help my brain think about the problem in its own terms by defining a range struct that could easily change:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Ord, Eq, PartialOrd)]

struct Range {

low: usize,

high: usize

}

impl Range {

fn contains_whole_range(&self, other: &Range) -> bool {

self.contains_low(other) && self.contains_high(other)

}

fn contains_low(&self, other: &Range) -> bool {

self.low <= other.low && other.low <= self.high

}

fn contains_high(&self, other: &Range) -> bool {

self.low <= other.high && other.high <= self.high

}

fn expand_higher(&self, other: &Range) -> Range {

Range { low: self.low, high: other.high }

}

fn expand_lower(&self, other: &Range) -> Range {

Range { low: other.low, high: self.high }

}

fn expand(&self, others: &Vec<Range>) -> Range {

let mut expanded_self = *self;

for range in others {

if self.contains_whole_range(range) {

// self.

continue;

}

if range.contains_whole_range(self) {

expanded_self = *range;

}

if self.contains_low(range) {

expanded_self = self.expand_higher(range);

}

if self.contains_high(range) {

expanded_self = self.expand_lower(range);

}

}

expanded_self

}

}

I don't know if others find it humorous. But I do get a good internal giggle (expressed

outwardedly with a swift short exhale of air from my nose) reading the expanded_self

variable name. Often, when I'm programming, I tend to anthropomorphize my program and computer.

So seeing the variable name beckons the image of a meditative monk, perched upon the binary towers

of the bit fields, reaching out with their mind's eye. Grasping at the electrical flow around them

and bending the silicon's fluctuations in their service.

My faith was smaller than a mustard seed here though, and so I stopped trying to move that mountain top temple and took a break to do my morning workout and eat breakfast. Then, I amused myself briefly by seeing if there was space within the computers internal universe to just hash everything:

// This _would_ work if we had infinite memory and time.

let mut in_range = HashSet::new();

for rule in rules {

for i in rule.low..=rule.high {

in_range.insert(i);

}

}

println!("{:?}", in_range.len());

There was not.

Hey, just because I anthropomorphize the computer doesn't mean that I'm always nice to it. I ended up wrapping up with a very inefficient (but not hash table inefficient levels) solution 2 minutes before it was time for me to head to work. Still, I wrapped up before work, so I was feeling alright.

fn p2(raw_data: &str) {

let rules: Vec<Range> = raw_data.lines()

.take_while(|line| !line.is_empty())

.map(|line| {

let mut raw_range = line.split("-");

let low: usize = raw_range.next().expect("couldnt read low").parse().expect("couldnt convert low");

let high: usize = raw_range.next().expect("couldnt read high").parse().expect("couldnt convert high");

Range { low, high }

}).collect();

let mut ranges = rules.clone();

ranges.sort();

let mut the_rules = rules.clone();

the_rules.sort();

let mut new_rules = Vec::<Range>::new();

// For each rule

// expand it to include any ranges in the other rules

// deduplicate ranges that should now be the same

for rule in &the_rules {

let mut new_rule = *rule;

for _ in &ranges {

new_rule = new_rule.expand(&ranges);

}

new_rules.push(new_rule);

}

new_rules.sort();

new_rules.dedup();

let mut ids_in_ranges = 0;

for range in new_rules {

ids_in_ranges += range.high - range.low + 1;

}

println!("{:?}", ids_in_ranges);

}

Though, this code certainly isn't anything to be proud of. Because I didn't rub the two awake neurons in my head together fast enough, the idea to sort the ranges by their lower range and only have to do one sweep across the rules during the expansion phase stayed cold. At least until a coworker mentioned sorting the ranges. Then it lit up long enough for me to consider tweaking my code, but was tamped down by the cold wind of you're on company time and have a todo list longer than these ranges.

Even still. Useless loops aside, the rules expanded, combined, and gave me my answer all the same. So I was content. Rested even! Ready to tackle the next day the moment it dropped.

Day 6 - in which I am smug about my solution ↩

Day 6 was, besides day 3's wallslamming, another case of fighting with rust more than actually implementing the solution itself. As per usual, the first part was done within a half hour, and then part 2 took up another hour and some change. The problem, strangely enough, seemed to be one which people's ability to transpose their thinking directly impacted their ability to solve.

The problem was, well, a set of problems. Math problems specifically. Cephalopods math! I quite enjoyed this one, and for the first problem set used a list of iterators to advance along the "block" of numbers one column at a time to compute the result based on the operator in the last row:

123 328 51 64 45 64 387 23 6 98 215 314 * + * +

The data was taken one "column" of numbers, top to bottom, at a time:

let lines: Vec<Vec<&str>> = raw_data.lines()

.take_while(|line| !line.is_empty())

.map(|line| {

line.trim().split(" ").map(|raw| raw.trim()).filter(|raw| !raw.is_empty()).collect()

}).collect();

let copy = lines.clone();

let ops = copy.last().expect("cant get op line");

let rows_of_numbers_count = lines.len() - 1;

let mut cursors: Vec<_> =

lines.into_iter()

.take(rows_of_numbers_count)

.map(|split_line| split_line.into_iter())

.collect();

let mut sum = 0;

for op in ops {

match *op {

"+" => {

for i in 0..rows_of_numbers_count {

let num: usize = cursors[i].next().expect("no next number").parse().expect("couldnt parse it");

sum += num;

}

}

"*" => {

let mut tmp = 1;

for i in 0..rows_of_numbers_count {

let num: usize = cursors[i].next().expect("no next number").parse().expect("couldnt parse it");

tmp *= num;

}

sum += tmp;

}

_ => unreachable!()

}

}

println!("{:?}", sum);

As I said, this only took 30 minutes to slap together. A solid chunk of which was taken up by

fighting with the compiler complaining about my .split in various places, and not

knowing what type I wanted the vectors to be inferred as. I felt pretty good about having a list

of iterators though, it seemed like a natural way to progress along the input one block at a time.

Part 2 didn't really change the problem itself, but rather changed the way you had to parse it. Rather than reading each column of numbers horizontally downward. Instead, we now had to read each individual character column as the number itself. So, rather than this

123 45 6 *

Meaning 123 + 45 + 6, it now became 356 + 24 + 1. Like I said,

it took about an hour to put together a solution, but only because rust fought me tooth

and nail against what I wanted to do and I had to come to a compromise with it.

That said, the compromise I reached was still very pleasant feeling to that part of my

brain that says you were clever, good job and proceeds to laugh like Anya from Spy x Family,

or haughtily Umus like Nero from Fate.

Umu! In essence, I started at the top right "corner" of the string, and then walked down the column collecting each digit as if I were parsing it for tokens. Then, when I reached an empty string or an operator, I'd parse the collected tokens so far into a number and either append it to the problem set, or perform the actual operation against said collected set.

fn p2(raw_data: &str) {

// white space is now significant

// but the operator defines the boundary leftmost part which should help.

// but maybe the simpler thing to do is to just transpose the input itself

let (matrix, rows, cols) = make_matrix(raw_data);

// read right to left

let mut numbers_in_problem: Vec<usize> = Vec::new();

let mut total = 0;

for col in (0..cols).rev() {

// Most significant digit is at the top, so read top to bottom

let mut number = String::with_capacity(rows);

for row in 0..rows {

// Do we have an operand?

let operand_row = row == rows - 1;

match (matrix[row][col], operand_row) {

(' ', true) => {

// end of the number we're building.

if number.trim().is_empty() {

numbers_in_problem = Vec::new();

continue;

}

let number_value: usize = number.trim().parse().expect("couldnt convert number!");

numbers_in_problem.push(number_value);

number = String::with_capacity(rows);

},

('+', true) => {

let number_value: usize = number.trim().parse().expect("couldnt convert number!");

numbers_in_problem.push(number_value);

total += numbers_in_problem.into_iter().sum::<usize>();

numbers_in_problem = Vec::new();

number = String::with_capacity(rows);

},

('*', true) => {

let number_value: usize = number.trim().parse().expect("couldnt convert number!");

numbers_in_problem.push(number_value);

total += numbers_in_problem.into_iter().reduce(|a, b| a * b).expect("no numbers to multiply?");

numbers_in_problem = Vec::new();

number = String::with_capacity(rows);

},

(c, false) => {

number.push(c);

},

_ => unreachable!()

}

}

}

println!("{:?}", total);

}

What, you say, could I have been possibly fighting the rust compiler with on this? Well, you see how we're doing two for loops? I really wanted to write something like

let idx = row * rows + col

And then use that to index into the raw string splice rather than parse the data into a matrix first. I'm pretty sure that's the right calculation, and yet, no matter how I tried to squint at it, stare, turn my head, or levitate upon my mountain top visualizing the silicon, rust still proclaimed loudly

index out of bounds

I suspect that my issue relates to, as per usual, how rust thrusts the very awful reality of

how bad strings are to deal with into your face. Despite the data being ascii, I wonder if

trying to index without using .nth() or similar was my problem? I'm really not sure,

but after sighing and just going with the double parse and matrix, the answer was easily in hand.

At which point I went to bed. The next day I watched icub3d's solution and was intrigued to see him make iterator implementations for the block chunks. Very cool! 6 This was similar to what I wished to do at first, on a human level, before I narrowed my focus onto the top right corner and the walk-back. What I thought was most interesting though, is that seeing his solution, and the solutions of the reddit threads he showcased, was that most people seemed to try to parse the solution left to right in some manner still.

Whether it was collecting the "chunks" left to right, or transposing the input to then iterate across it left to right. It seems like few people deemed it prudent to start at the end and do as the cuttlefish do. But I think it makes a lot of sense to process the input right to left and top to bottom. It made it easy to treat the input as tokens and parse it at the end of each expression. The operators were natural periods to the sentence of digits after all.

As long as you get a solution it all works out though, at least for me that's generally my goal. Unlike last year, I'm not trying to teach myself rust, but rather just shake the dust off. So the goal is less learning focused and more oooh yeaah, that's how you do it focused. Which perhaps is why I feel significantly less pressure this year. Though that may be because there's only 12 days and the fear of falling behind is lower due to this. Speaking of falling though…

Day 7 - off by one falls to face ↩

Grids. The final frontier. Or at least, the start of the Tron Legacy movie, and of Day 7's

input! The first part of the problem was easy again. Takings 15 minutes of my time to

copy the matrix code and walk down the simulation of a beam of light starting at S

and splitting each time it ran into a ^ symbol as it traversed downward through

the grid.

['.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', 'S', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '^', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '|', '|', '^', '|', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '|', '|', '.', '|', '.', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '|', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '.', '.'] ['.', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '|', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '.'] ['.', '|', '^', '|', '|', '|', '^', '|', '|', '.', '|', '|', '^', '|', '.'] ['.', '|', '.', '|', '|', '|', '.', '|', '|', '.', '|', '|', '.', '|', '.'] ['|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '^', '|', '|', '|', '^', '|'] ['|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '.', '|', '|', '|', '.', '|']

It's always fun when debugging involves visualizing the input. Not that that there was much debugging at all, counting how many times the beam split is pretty simple. At least, by simulating the input it is:

fn p1(raw_data: &str) {

let (matrix, rows, cols) = make_matrix(raw_data);

let s_location = matrix[0].iter().position(|c| *c == 'S').expect("Could not find start in first row");

let mut beams = vec![s_location];

let mut number_of_splits = 0;

for r in 1..rows {

for c in 0..cols {

// A beam in the current list of beams has hit a splitter

if matrix[r][c] == '^' && beams.contains(&c) {

number_of_splits += 1;

beams.retain(|idx| *idx != c);

if c > 0 {

beams.push(c - 1);

}

if c < cols {

beams.push(c + 1);

}

// The problem makes a point of noting merges so, make sure we

// nix double counts as needed.

beams.sort();

beams.dedup();

}

}

}

println!("{:?}", number_of_splits);

}

You might think: "well won't it split based on how many splitters there are?" Sort of! But the trick comes when beams merge together, thus reducing the potential beams. Not to mention that, just because a splitter is hanging out somewhere, there might not be a beam that actually traverses far enough from the starting area to hit it. That would make an interesting "part 3" actually, how many splitters did we not hit. 7 Anyway.

A couple of compiler errors about moved values and the need to dereference my c

value later, I had a working solution and it was only 12:16am! Woohoo! At this rate I'll be

going to bed nice and early! Right?

Right?

At 1:56am I gave up on part 2. And, at 2:18am, I submitted my correct solution and went to bed.

Getting nerd sniped and mulling code over in the dark cool is a wonderful feeling. I actually really like at how often Advent of Code invokes that "just one more..." sort of feeling in me. That obsessive itch that day jobs only scratches on rare occasion. As always, the problem was just that my order of operations was slightly off, and that I needed to stare at the incremental data a few more times.

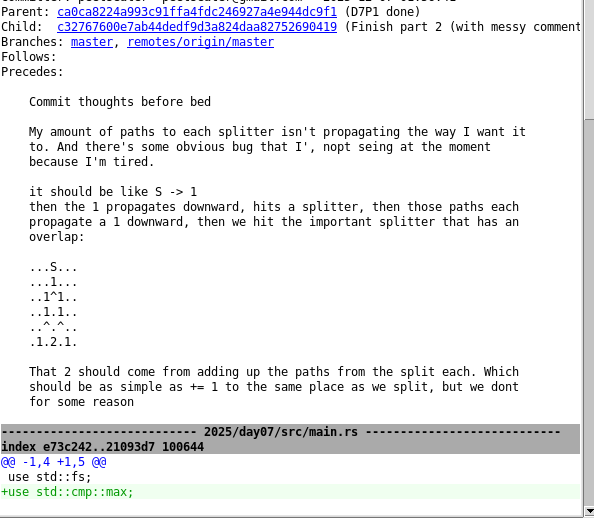

Part 2 was no longer about how many times the beam of light was split, but rather, how many timelines exist for a single beam to follow a path. The amount of Steins;Gate jokes I made to myself while working on this began to rival the number of splitters.

My solution basically involved keeping a track of how many lines had converged together, and then propagating that number forward on each step of the simulation. Doing this meant that we could, besides the initial parse, do this in one iteration of the input plus one last summation across each individual path at the very very end. Codewise, it's a bunch of statements susceptible to off by one errors and a parrallel universe in which the characters of the input live duel lives as numeric values:

fn p2(raw_data: &str) {

let (matrix, rows, cols) = make_matrix(raw_data);

// Draw the world lines, this will give us our graph.

let mut worldlines: Vec<Vec<usize>> = Vec::with_capacity(rows);

for r in 0..rows {

let mut tmp: Vec<usize> = Vec::with_capacity(cols);

for c in 0..cols {

tmp.push(0);

}

worldlines.push(tmp);

}

let s_location = matrix[0].iter().position(|c| *c == 'S').expect("Could not find start in first row");

worldlines[0][s_location] = 1;

let mut beams = vec![s_location];

for r in 1..rows {

for c in beams.iter() { (A)

worldlines[r][*c] = max(worldlines[r - 1][*c], 1);

}

for c in 0..cols {

// A beam in the current list of beams has hit a splitter

if matrix[r][c] == '^' && beams.contains(&c) {

let how_many_lead_to_this_beam = worldlines[r - 1][c];

beams.retain(|idx| *idx != c);

if c > 0 {

beams.push(c - 1);

worldlines[r][c - 1] += how_many_lead_to_this_beam;

}

if c < cols {

beams.push(c + 1);

worldlines[r][c + 1] += how_many_lead_to_this_beam;

}

beams.sort();

beams.dedup();

} else if beams.contains(&c) {

// this was resetig us from 1 1 to 1 0 (B)

// worldlines[r][c] = worldlines[r - 1][c];

}

}

}

let number_of_world_lines = worldlines[rows - 1].iter().sum::<usize>();

println!("{:?}", number_of_world_lines);

}

Two things about this code. One, is that A was the key to the bug I gave up

on at 2am being solved. And two, B was basically doing the same thing as A

but causing other weird behavior for my cumulative insanity. Once I moved the beam propagation

for each running beam up to its proper home, I stopped getting a grid of 1s and 0s and started

getting the actual data I expected:

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0 , 0, 0 , 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 0 , 0, 0 , 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 0 , 0, 1 , 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 0 , 0, 1 , 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 0 , 1, 1 , 2, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 0 , 1, 0 , 2, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 1 , 1, 3 , 2, 3, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 0, 1 , 0, 3 , 0, 3, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 1, 1 , 4, 3 , 3, 3, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 0, 1, 0 , 4, 0 , 3, 3, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0] [0, 0, 1, 1, 5 , 4, 4 , 3, 4, 1, 2, 1, 1, 0, 0] [0, 0, 1, 0, 5 , 0, 4 , 3, 4, 0, 2, 0, 1, 0, 0] [0, 1, 1, 1, 5 , 4, 4 , 7, 4, 0, 2, 1, 1, 1, 0] [0, 1, 0, 1, 5 , 4, 0 , 7, 4, 0, 2, 1, 0, 1, 0] [1, 1, 2, 1, 10, 4, 11, 7, 11, 0, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1] [1, 0, 2, 0, 10, 0, 11, 0, 11, 0, 2, 1, 1, 0, 1]

The final row provides us both with the resting place of each beam's trajectory, and with how many worldlines could potentially take us there. One green banana later and I had microwaved myself to victory 8.

I also started writing this blog post before Day 7 appeared. These things tend to take time to put together, and I should probably keep a running set of notes if I want to do a Day 12 retrospective as well. But for now at least, I'm pretty happy with how these things are going, it's a lot of fun to think about these things with people, watching others chat and solve them in their own ways is fun too